China's government has approved genetically modified crops. Researchers are enthusiastic. Because this clears the way for the use of the plants in agriculture, many say that it is now possible to work more intensively on tastier, more pest-resistant and better adapted to global warming varieties.

Since the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture published preliminary guidelines on January 24, 2022, scientists have hurried to submit applications for the use of their genetically modified plants. This includes the development of wheat varieties that are resistant to the fungal disease of real mildews and which have been described this week in the journal "Nature".

"This is very good news for us. It opens the door to commercialization," says plant biologist Caixia Gao of the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, who is one of the authors of the paper. Others also consider the decision a big step forward for China. The new rules would take research from theory to practice, says Jin-so Kim, who heads the Center for Genomics at the Institute for Basic Research in Daejeon, South Korea.

China's new regulations are more conservative than those of the United States; There are no genetic engineering plants that have small changes that are similar to those that could arise in a natural way. But they allow more than the guidelines of the European Union, according to which all genetically modified crops are considered genetically modified organisms (GMO).

On a small scale, field tests with genetically modified plants are allowed.

Genetically modified crops are being developed with the help of technologies such as the CRISPR-Cas9 gene scissors, which can make small changes to the genetic sequence. They differ from genetically modified plants, in which, as a rule, whole genes or DNA sequences from other plant or animal species are inserted. However, so far in China they fall under the same legislation as genetically modified organisms.

At the moment it can take up to six years before you get approval for the biological security of a genetically modified plant in China. The new guidelines could shorten the approval period to one to two years, say.

Genetically modified crops require extensive, large-scale field trials before they can be used. The new guidelines stipulate that developers of genetically modified plants that do not pose risks to the environment or food safety only need to provide laboratory data and carry out small-scale field trials.

However, some criticize that the guidelines are ambiguous. They apply to crops in which genes remove genes or change individual nucleotides with the help of genetic engineering. However, it is not clear whether they also apply to crops in which DNA sequences from other varieties of the same type were introduced. "We have to confirm whether this is allowed", because it is important that the rules are clear, says Chengcai Chu, a rice geneticist at South China Agricultural University in Guangzhou.

Researchers are already planning to focus their work more on the development of new plants that are useful for farmers. For example, Jian-Kang Zhu, a plant molecular biologist at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, wants to develop genetically modified varieties that bring higher yields, better resilience to climate change and better response to fertilizers. Others are preparing applications for rice, which is particularly aromatic, and for soybeans, which have a high content of oleic fatty acids, which could produce an oil low in saturated fat.

China has already conducted fruitful research on genetically modified crops.

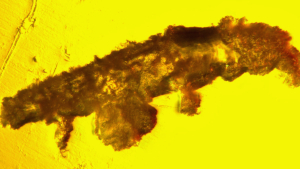

Gao's powdery mildew-resistant wheat could be one of the first to be approved. In 2014, the plant biologist and her team used gene editing to turn off a gene that makes wheat susceptible to the fungal disease, but found that the changes also inhibited the plant's growth. However, one of their edited plants grew normally, and the researchers found that this was due to the deletion of a chromosome section that did not suppress the expression of a gene involved in sugar production.

Since then, the researchers have been able to remove the same part of the chromosome and the gene that makes the plant susceptible to mildew, and thus create fungal -resistant wheat varieties that do not suffer from growth disorders.

"This is a very comprehensive and well-done job," says Yinong Yang, a plant biologist at Pennsylvania State University in University Park. It has far-reaching effects on almost all flowering plants, he says, because powdery mildew can infect about 10,000 plant species. However, the data on wheat growth is based on relatively few crops, most of which were grown in greenhouses, adds plant geneticist David Jackson of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. They still have to be confirmed with the help of larger field trials.

"Studies like this are proof of China's successful research in the field of genetically modified crops," says Penny Hundleby, a plant scientist at John Innes Center in Norwich, Great Britain. The new regulations would lead to China fully exploited his academic lead.