Eating regularly at night increases the risk of getting diabetes type 2 diabetes. Only taking meals during the day helps to contain this danger, even if the sleep rhythm is shifted. To the conclusion, a team around the doctor Sarah Chellappa from the Harvard Medical School in Boston came in the specialist magazine "Science Advances".

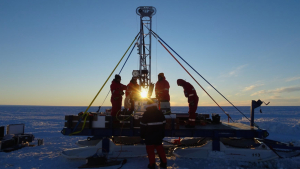

The group carried out a small study with 19 participants. The subjects-seven women and twelve men-spent two weeks in a strictly controlled laboratory environment in which the light-dark phases are moved further and further until they differed from natural times of the day. This forced disturbance of the sleep-wake rhythm served to simulate the effects of nightly shift work.

Ten participants received their meals adapted to the changed daily routine, i.e. also during the natural night hours. The remaining nine subjects were only allowed to eat during the natural times of the day, despite the shifted sleep-wake rhythm.

The metabolism is irritated by late dishes.

In the first group, which ate at night, blood sugar levels increasingly decoupled from core body temperature, the team observed. While the body temperature rose and fell in a constant rhythm, the blood sugar fluctuations were out of sync by twelve hours. The researchers see this as a sign that the participants' internal body clocks diverged. There was a mismatch between the central clock in the brain and the organ's own clocks of the liver or intestine, according to the study. "The data show that while the central pacemaker was still set to Boston time, some peripheral clocks, for example in the liver, had dramatically changed to a new time zone," says Frank Scheer, one of the scientists involved.

In addition, the participants who took nightly meals could only control their blood sugar levels to a limited extent. After eating, he jumped up more strongly and remained elevated longer than with the others; the release of the blood sugar-lowering hormone insulin began with a delay. Over the entire observation period, these people had an increased mean blood sugar level.

On the other hand, the subjects who only had food during natural times of the day failed to materialize - despite simulated night work. There was no decoupling of the body clocks or poorer blood sugar control.

It has long been known that frequent or permanent shifts in the sleep-wake rhythm, for example due to shift work, increase the risk of diabetes. Based on the current findings, the scientists around Sarah Chellappa suspect that this is mainly due to the changed eating behavior of affected persons. If night workers continued to limit their meal times to the natural light phase, this could potentially help prevent disruption of sugar metabolism and help keep the internal body clocks in sync, the team writes.