The first to hear about the supposed discovery were the spectators of the Cypriot local television. On January 7, 2022, the virologist Leondios Kostrikis announced in a program that his research group at the University of Cyprus had identified several SARS-COV-2 geneomas, which wore elements of the delta and omikron variant.

»Deltacron« was discovered. Under this name, Kostrikis and his team uploaded 25 of the sequences to the GISAID database that same evening. Another 27 followed a few days later. On January 8, the financial news agency Bloomberg picked up on the story. Deltacron became international news.

Reactions from other scientists were not long in coming: Many experts explained both on social media and in the press that the 52 sequences do not indicate a new variant, not the result of a recombination, the exchange of genetic information, but a lot More profane explanation: You are probably due to the contamination of samples in the laboratory.

"There is no #Deltacron," tweeted Krutika Kuppalli, a member of the World Health Organization's Covid-19 team based at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, Jan. 9. "#Omikron and #Delta did NOT form a super variant."

Spreading false information

How a few Sars-CoV-2 sequences became the focus of a brief and intense scientific controversy is an interesting story. And it's complicated.

Kostrikis himself emphasizes that aspects of his original hypothesis have been misinterpreted. In addition, he never said that the sequences were an intersection of omikron and delta - despite the confusing name that some media interpreted in such a way that the sequences were a recombination. Three days after the sequences were uploaded into the database, he has now made the entry invisibly in order to wait for further analyzes.

Given the more than seven million Sars-CoV-2 genomes uploaded to the GISAID database since January 2020, some sequencing errors shouldn't come as a surprise, says Cheryl Bennett, a staff member at the GISAID Foundation's Washington, D.C. office. Especially not if they come from laboratories that would have to work under considerable time pressure.

Laboratory contamination occurs frequently

The "Deltacron" sequences were obtained from virus samples that Kostrikis and his team received in December as part of a study to spread Sars-COV-2 variants in Cyprus. The researchers noticed that some viruses in their spike protein had a genetic signature that resembled Omikron. His original hypothesis was that Delta virus particles-regardless of Omikron-had developed such mutations in Spike gene, Kostrikis writes in an email to "Nature".

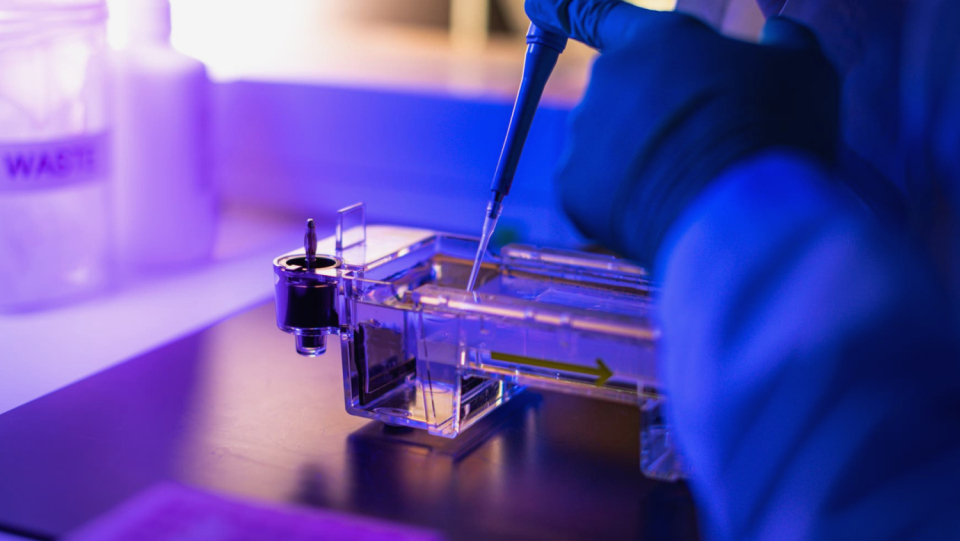

As soon as the topic made the rounds in the media, other experts who are also working on genetic sequencing and Covid-19 spoke up, pointing to laboratory errors as an alternative explanation. The sequencing of each genome depends on primers – short, artificially produced pieces of DNA that serve as the starting point for sequencing by binding to the target sequence.

However, Delta has a mutation in the spike gene, which limits the binding ability of some primers, which makes it difficult to sequence this genome area. Omikron does not have this mutation. So if omikron particles were mixed into the rehearsal by contamination, the sequential spike gene could be similar to that of Omikron, says Jeremy Kamil, virologist at the Louisiana State University Health Shreveport. This type of contamination is "very, very common".

Kostrikis counters that if "Deltacron" had been created by contamination, sequencing would have yielded Okron sequences with delta-like mutations, since Omikron has its own mutation that hinders the primer. On social media, his result was hastily dismissed as contamination, "without anyone taking full account of our data or providing clear evidence to the contrary."

Science is self-correcting.

But assuming that the result was actually not due to contamination, Kostriki's colleagues argue that the mutations his team has identified are not exclusive to Omikron. Which is why the name »Deltacron« is not really appropriate.

In fact, there are countless sequences in the GISAID database that contain elements of sequences of other variants, says Thomas Peacock, virologist at Imperial College London. Such sequences "are constantly uploaded," he says. But no rumors about new mutations would have to be correct here, "because the press does not report so much about them".

"Scientists have to be very careful with what they say," explains a virologist who wishes to remain anonymous. »When we give something of ourselves, sometimes borders are closed because of it.« Kostrikis says he takes the critical reactions from the scientific community seriously and plans to have his research results reviewed when they are published.

For some, such incidents also grows the risk that researchers will become more reserved in the future in terms of rapidly sharing their results. That would also not be desirable, says Jeremy Kamil. "You have to give the scientific community the opportunity to correct yourself," says the virologist. "And in a pandemic you have to make the quick exchange of virus genome data easier, because this is the only way to find variants."

© Springer Nature 10.1038/d41586-022-00149-9, 2021