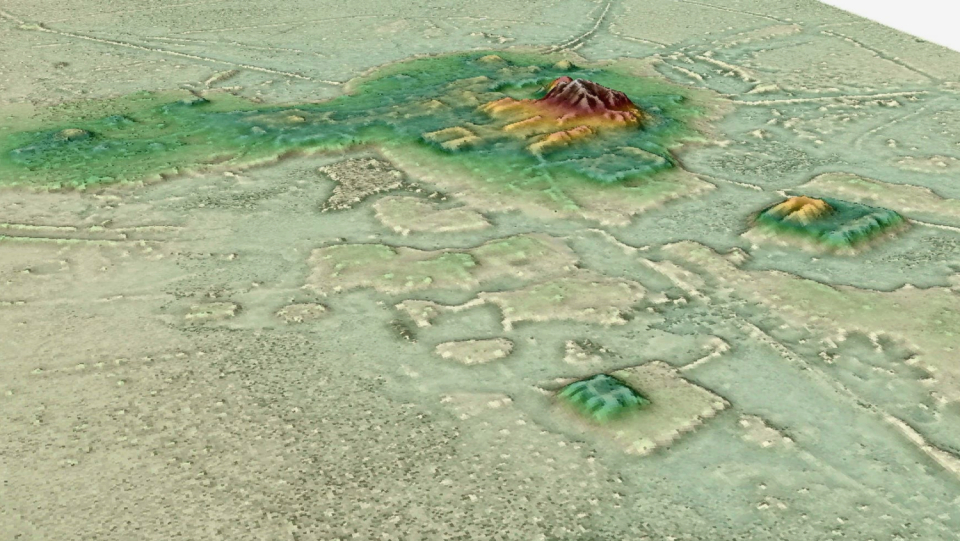

City-like settlements once flourished on hills in the southwestern corner of the Amazon Basin, as researchers found out with the help of the Lidar remote sensing method. About 1500 years ago, pyramids made of earth, built about 22 meters high, rose on the hills. In addition, the villages in the Bolivian lowland Llanos de Moxos were surrounded by miles of causeways.

It is "unbelievable" how complex the settlements were built, says Heiko Prümers from the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin, who recently published the discovery together with colleagues in "Nature".

"This is the first clear evidence that there were urban societies in this part of the Amazon basin," confirms Spanish archaeologist Jonas Gregorio de Souza of the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, who is not involved in Prümer's project.

The new study adds to a growing number of research reports that expose a 20th-century doctrine as false: the Amazon was by no means an untouched wilderness before the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century. Rather, complex societies with urban structures also developed there.

Have people lived in the Amazon area as a hunter and collector?

The river-crisscrossed Amazon basin is about the size of the United States. People have been living there for about 10,000 years. For a long time, the general research opinion was that the population roamed the country in small groups as hunters and gatherers, without having much influence on their environment. Although the first European visitors reported landscapes full of towns and villages, later travelers did not see anything like this.

In the 20th century, archaeologists countered the persistent rumors of sunken cities in the jungle with a very powerful argument: the nutrient-poor soil of Amazonia did not allow agriculture on a large scale, civilizations such as in Central America and Southeast Asia could therefore not have developed in the first place. However, with the turn of the millennium, doubts grew. Because how did the spots of nutrient-rich soils in the middle of the jungle explain themselves? And why did useful plants grow in dense clusters near them? Perhaps the Amazonian inhabitants had transformed their environment in pre-Hispanic times.

In 2018, this thesis was confirmed when hundreds of large, regularly shaped hills came to light when the rainforest is picked up. These structures indicated early organized societies that lived in one and the same place for a long time. But there were no clear evidence of settlements.

Traces of human habitation in Bolivia's Amazon basin

Since 1999, Prümers has been researching a number of possible settlement mounds in the Bolivian part of the Amazon basin, outside the dense rainforest. In the Llanos de Moxos, a large number of promising elevations, overgrown with trees, protrude from the lowlands, which are flooded during the rainy season.

Previous excavations had to reveal traces of settlement on such "forest islands", including the remains of the Casarabe culture, which was hardly researched after a small Bolivian village, which occurred around 500 AD. During one of their excavation campaigns, Prümers and his team came across something that seemed to be a wall. Such a building spoke for a permanent settlement in this place. The researchers also found graves, platforms and other references to a developed society. However, the dense vegetation ceiling made it difficult for archaeologists to explore the settlement structure of a site based on reading finds.

For some years now, the remote sensing technique Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) has offered an alternative. A laser scans the area in question from an aircraft. The transit times of the emitted light signals reveal the distance of the reflecting surface to the transmitter. The result is a topographical representation of the terrain flown over. Because enough laser pulses also reach the ground through the foliage, the plant cover can later be calculated out on the computer. Lidar thus reveals soil structures overgrown by vegetation. In 2012, a pre-Hispanic city came to light in Honduras, which was abandoned in the 15th century and abandoned to the jungle. It was assumed that the city ruins existed, but without lidar they would not have been found.

Casarabe sites are revealed by lidar.

In 2019, Prümers and his colleagues scanned six areas near proven Casarabe sites with a helicopter. Also on board: a lidar system. The result exceeded all expectations. Lidar covered 26 settlements in size and shape, including 11 sites that were not known until then. Prümers estimates that this measurement would have taken 400 years with Surveys on the ground.

On two of the hills were urban centers, each more than 100 hectares in size – three times the size of Vatican City. The lidar images showed walled complexes with wide, six-meter-high terraces. At each end of each platform, a cone-shaped pyramid made of earth towered up (see picture »Revealed by the laser«). What function the monumental facilities fulfilled remains to be clarified. Its construction, however, required a high degree of social organization. Probably the people lived in the wider area, causeways connected the sites with each other – even if the area was flooded during the rainy season.

"We have the idea of Amazonia as a green desert," says Prümers. But because civilizations also arose and flourished in other tropical areas, the archaeologist asks: "Why shouldn't there be such a thing here?«

Did people travel because the weather was different?

Radiocarbon dating has shown that the Casarabe culture disappeared around 1400. Why the settlements were abandoned after 900 years of use is still unclear. Prümers cites climate change as a possibility. The lidar measurements also revealed larger basins in the settlements, which may have served as water reservoirs in times of drought. However, pollen finds show that maize has been cultivated in this area for thousands of years. Apparently, the people had been farming permanently.

The discovery of pre -Spanish cultures gives Brazilian archaeologists Eduardo Neves from the University of São Paulo hope that "the usual view of archeology in the Amazon region will change". Because deforestation and intensive agriculture probably also destroy previously unknown archaeological sites. A stronger public interest could therefore lead to more protective measures.

In any case, the idea that the indigenous peoples were passive inhabitants of the Amazon basin before the arrival of the Europeans is outdated – Neves is convinced of this: "The people who lived there changed the landscape forever!«