The damp bamboo stands meters high. Its leafy roof lets only little light through. The sky is still covered with clouds that have survived the night rain. Between the bars, the path is so muddy in places that a shoe could easily get lost in it. Especially if you do not look down, but constantly look at the canopy of leaves, because there is a suspicious rustling there. The wind? A bird? Or is it finally that endangered creature for which the group boots through the mud of the Mgahinga National Park?

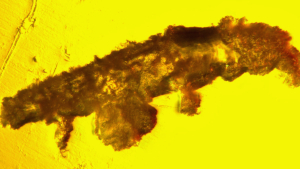

In the deep southwest of Uganda, some of the last remaining gold -sea cats (Cercopithecus Kandti) live in the world. The primates only occur in two small, separate populations: in the area of the Virunga massif and in the Gishwati forest. The Virunga massif includes Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the MgaHinga Gorilla National Park in Uganda.

What may sound like a large area has been getting smaller and smaller for decades. Since the 1950s, the forest has shrunk noticeably, and with it the animals are dwindling. In Rwanda, depending on the region, there have been 50 to 98 percent fewer specimens of Cercopithecus kandti, while in Uganda the population fell by about 40 percent between 1998 and 2003 alone. Not quite 1000 monkeys still live there. And even if the total number seems stable at the moment, experience teaches us that action must be taken to ensure that the bushy primates survive.

Conservationists, park managers, researchers and citizens from the three home countries of the Golden Sea cats have therefore developed a regional action plan in 2018, the Conservation Action Plan, CAP for short. The vision: "By 2026, viable golden sea cat populations should thrive in their entire distribution area." And the kick-off year 2021 was promising.

Sea cats rush, hum, squeak, drip, whir, and whip their way to the gold.

"Attention, smoothness." "Attention, giant earthworm." "Attention, hole." Shouldered with their assault rifles to protect them from sometimes aggressive elephants and buffaloes, the rangers dressed in camouflage colours walk almost light-footed through the forest. The rest of the group gratefully reaches for the bamboo canes and, sprinkled with drops, slid one foot in front of the other. It is humid but not stuffy in this part of the forest. Gloomy but colourful. Quiet, but not silent.

The welding film, which covers the entire body, and the breeze that passes through the pipes, cool. Despite clouds and thickets, one perceives different shades of green. The grass next to the path is reminiscent of the forest green at home, the pipes of the bamboo are more yellowish, covered here and there with a moss-green, fluffy layer. And again and again polka dots of fern green, lime green, jungle green. It rustles, buzzes, squeaks, drips, buzzes, squeaks.

This forest was once part of a big picture. At that time, the monkey populations lived in a coherent area, but was finally separated by the construction of a street between the two largest cities in northwestern Rwanda and increasingly spreading agriculture. The Congolese government in turn had reduced the Virunga-Park in turn, the area around the area is now one of the most densely populated areas in Africa. For this, forest in lower layers had to give way and the only zone with trees, the fruits of which the primates eat. In the Republic of the Congo it was cattle shepherds that added the forest in the late 1950s, and in the mid -1990s refugees from Rwanda who needed wood as fuel. In Uganda alone, it remained comparatively quiet - although part of the forest was also snatched from the forest dwellers and awarded people.

Today, the zone with bamboo (Yushania alpina) at 2000 to 2900 meters, in some places even 3300 meters altitude is the most important habitat for Uganda's golden monkeys. Between the high branches and in the canopy they feel comfortable. When the sun shines strongly or it gets too warm up there, they move to the ground. And the bamboo is not only their home, they also like to eat it because it is rich in proteins.

True, some golden sea cat does not disdain either fruits or insects. The animal must remain flexible when the habitat changes. According to previously unpublished data, the primates feed on a total of more than 100 different food plant species. But at Mgahinga, bamboo is at the top of the menu.

The observations of the MGAHINGA rangers are extremely valuable

A clearing in the middle of the thin rods. And clearly visible, right at the edge at a height of about three meters, a bushy, red-furred golden monkey with golden back fur, which first squats carefree and then jumps surprisingly gracefully and quickly to the next branch. "There are more where she's going!" says one of the rangers. He is right.

Suddenly they are everywhere. Golden sea cats on the right, on the left, in the tops. Only a few rest, most play, clean themselves or their peers, feed, jump, practice in conversation. Mothers carry young animals on their backs in order to gently set them down on the adjacent branch for a short time, stretch themselves for a leaf and put it in their jaws. A monkey eases itself in the tree, just in time you jump to the side. "There's no 'golden shower' today!" That's what the rangers call the pipi rain. The zoo is different.

The forest is on the move. Gold sea cats climb up higher, deeper down, scurry from one tree bus rod to the next. The long cock helps to keep balance. The entire monkey group continues high up while playing, cleaning, feeding. The entire group of people stumbles, their heads in the neck and blinded from the sky, with his eyes crazy on the floor.

Kashingye is the name of this group of monkeys, which is completely settled in the Mgahinga. 60 to 100 individuals are among them. There is also the Kabacondo group with an estimated 100 to 150 specimens. They are still getting used to tourists and migrate to the Republic of Congo from time to time.

Despite their protection status, researchers have so far carried out and published only a few examinations of gold -sea cats.

The work of the rangers in the MGAHINGA are therefore particularly valuable.

Every day they see how their protégés are doing.

Are the animals in good health?

Where do they move and when?

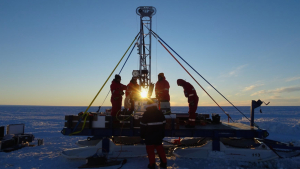

How does tourism work?

"We observe the behavior, take feces, pursue suspected tracks, examine food residues and listen to their various shouts," says Moses Turinaw, the supervisor for tourism in the MGAHINGA GORILLA National Park.

With the help of calls, the animals would mostly communicate, but sometimes also through visual signals.

Since 2019, The Kashingye Group has experienced frequent visits.

On their forays, Turinawe and his team have learned a lot about the behavior of the Golden Sea cats in recent years. "A dominant male determines where the group eats or sleeps," the supervisor explains, "but the female also defends her territory herself." In addition, the males would have the chance to mate with each female of the group – but it is the females who court the males.

Copulation is usually done when food is available in abundance. "The females give birth to their first young at the age of about five years, the gestation period is 140 days," says Turinawe. "The newborns are completely dependent on the mother for food and protection," he continues. Weaning, he and the team have observed, occurs at about 24 to 30 months. Accordingly, there are only every two to four and a half years offspring. For an endangered species quite a long time. The good thing: The Kashingye group is teeming with young animals, the attacks by humans have decreased, the family is growing.

Measured on their skills, gold -sea cats are "very special primates," says Turinaw, who is involved in the Conservation Action Plan. As a tourism officer, he investigates the question of how more people attract themselves to the park and distribute the income without the animals being disturbed in their natural environment. A central aspect of the cap.

The Kashingye Group has been receiving regular human visits since 2019. Getting golden monkeys used to visitors takes more than ten years, "so it takes a lot of time," says Turinawe. For chimpanzees or gorillas, this takes only half as long. Currently, the government shares part of the tourism revenue with local communities, ten percent goes to Rwanda, according to the CAP report, and five percent each to Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The money will be used to build schools, clinics and roads, maintain buffalo walls and ditches and support private households so that fewer people poach illegally in the national parks.

You want to draw more visitors and encourage local commitment to protect gold-sea cats.

For Turinawe and his colleagues, it is clear that the shares are too small and not comprehensibly distributed. "The distribution of tourism revenues needs to be revised to ensure more resources to meet the urgent needs of the community," the CAP report states. In order to have more funds available, it is important to market the golden monkeys more strongly and to accustom more animals to humans. Thus, the individual groups could be smaller, which would benefit the monkeys, but at the same time more people could visit the Puschel primates.

The Virunga mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei), which are also threatened, show how successful such a concept can be. Instead of keeping people away from them, they have been heavily involved in protection; including veterinary care and close monitoring of individual animals. The result: in 1981 there were fewer gorillas in the region than ever before, by 2011 there were about 400 animals, and in 2018 there were already more than 1000 free-living mountain gorillas worldwide.

What natural protectors, park managers and researchers have learned: Without the support of the local communities, it will be difficult. "Good relationships between the parks and people all around are an important step," says the report. People who live near the park harvest bamboo for firewood, web material and bean sticks. You need the plants to survive as much as the monkeys. In this respect, it is important to search for and provide alternative, sustainable and accessible sources for local people.

Considering the number of animals and assaults, there is still a lot to do. Educational programs have been around for decades, but they are few; moreover, they are confined to a few schools and villages. Also, there are hardly any job alternatives to agriculture near the golden monkeys. Nevertheless, the conditions for the success of the plan could be worse by 2026. The majority of residents say they would benefit from living near the parks. And if not as imposing and human-like as gorillas, golden monkeys are at least fluffy, cute and cheeky playful like toddlers.

It has cleared up over the forest by now. At first, a sea cat scurries from rod to rod, under its weight the pipes bend to the side. Then the monkey descends and squats down. He looks cozy with the fur, in which drops of beads. And like a gourmet, with his round belly. He bites off the bamboo with relish. Still on the way back, it's as if his smacking is echoing through the forest.