Victoria Morris was considered one of the first sailors on her yacht of swords. That was in the summer of 2020, and for the biologist it was a traumatic experience that later told the British newspaper "The Guardian". When she "Mayday: Orca Attack!" Was radioed, the experienced seafarers of the coast guard initially believed in a joke. But the whales coordinated their action with shrill whistles, which in combination with ramming, wind and waves had resulted in a scary background, Morris reported. It shouldn't remain the only event of this kind.

The attack on 29 July 2020 will be followed by 235 more. This emerges from a statistic from »Iberian Orca«. Researchers founded the working group after the first incidents in order to record and analyse the new behaviour and to answer the essential questions: What is behind the behaviour of killer whales (Orcinus orca) and how best to deal with it?

The orcas mostly attack larger sailing boats

Orcas and boats clash from time to time – for example in the Southern Ocean or off the coast of Alaska and British Columbia. But until 2020, there were only two reports of killer whales attacking boats worldwide: In 1972, a group of whales sank a yacht near the Galapagos Islands*, and a similar incident was repeated off the coast of Brazil in 1976. However, since these animals had not tried to push ships away, the Gibraltar killer whales are considered to be the first population to prevent boats from continuing their journey in a coordinated group.

Most incidents occur in the Gibraltar street, others in Portuguese and Spanish waters to Galicia. In 2022 it started in January, at the end of May 2022 there were two within 24 hours. The incidents took between 30 minutes and two hours. The animals are particularly targeting larger sailing boats.

Profile: Killer whales

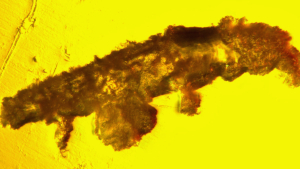

Killer whales (Orcinus orca) grow an average of seven to eight meters in length and can weigh more than six tons. The orcas of the Strait of Gibraltar and the Gulf of Cádiz are the southernmost subpopulation of the Northeast Atlantic killer whales.

Orcas live in matrilinear family groups: an old female - the matriarch - leads her group out of her sons and daughters as well as the descendants of the daughters. These family groups remain stable over long periods, at some point one of the daughters with their descendants leave the group.

The stock of the Strait of Gibraltar consists of five families with about 50 members. Genetic studies have shown that although they belong to the north-eastern Atlantic stock, they have long been isolated. The photo identification catalogues also show that there is hardly any exchange between the Iberian families and others.

All eyewitnesses report that the Orcas had never tried to attack a person or sink a boat - obviously they just wanted to move the boats to turn around. The fast whales would have cooked from aft, then rammed the yacht and specifically attacked the rowing system, it is said. Researchers also found dentures on Kiel and Bug.

Marine biologist Ruth Esteban of the Madeira Whale Museum and marine scientist Alfredo López of the University of Santiago, who belong to »Iberian Orcas«, call this »disruptive behaviour«. If the boat occupants countersteered, this caused the marine mammals to act more strongly – similar to dogs that initially only bark and gradually snap, explains Esteban. In addition, the whales seem to understand the function of the rudder, says López.

A possible cause: the struggle for food

It is quickly explained why the attacks take place between January and October: In search of food, the tooth whales appear regularly in the area from January. Then the red tunfish (Thynnus Thunnus) comes from the Atlantic through the Gibraltar street for reproduction to the Mediterranean. After the tunfish season in October, the whales disappear again in the open Atlantic.

It is also known which animals seek the conflict. The interactions with the yachts are currently based on 14 whales from four different family groups, explains López. This group, called GLADIS by the biologists, consists of a grandmother, two mothers, their offspring and two other individuals.

Obviously, the families learned from each other, says Alfredo López. This type of learning - called "horizontal learning" - within a society is a cultural achievement. López emphasizes that the behavior of the Gladis group is not aggressive. The animals did not want to injure people or sink boats. López is convinced that this happens. In May 2022, a Moroccan fisherman had lost his little boat for the first time: after Orcas had jostled him, the presumably dilapidated boat struck and sank while his colleagues towed it. The actual intention of the sword whales is to prevent certain types of boats from continuing.

The observations lead back to the overarching question of why some animals have passed to attack. One guess: the orcas are now experiencing the fishermen and thus larger boats as strong food competitors for Tunfish. The region has been fishing in the region for centuries and the Gibraltar Orcas have come to terms with the fishermen; Some whale families have learned, for example, to pick the catch directly from the hooks when catching up the linen. But tunfish is becoming increasingly popular, which endangers the stocks.

Researchers largely agree that the Gibraltar sword whales are under severe stress. The orcas are disturbed or injured by fishing boats, sometimes they even lose their calves because they get caught in the nets. Inheritance fishermen also try to drive away the black and white marine hunters with stone throws, sometimes even with electric shockers that actually serve to anesthesize the tunfish on the hook, as Jörn Selling from the Firmm Foundation has heard more often. He has been on site for around 20 years and watches regularly at Whale Watching how whales and fishermen interact. = "Https:>

Attention Orca – a code of conduct for boaters

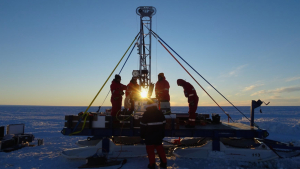

So what to do? A team led by marine scientist Neus Perez Gimeno had already recommended in 2014 to develop a plan to protect the endangered Iberian orca population due to overfishing and the simultaneous increase in whale watching tours. Nothing happened for two years.

In 2016, a group led by Ruth Esteban and Andy Foote again asked the Spanish government to create a management plan to set up a seasonal protected area in which activities that cause underwater noise are restricted. In addition, these orcas should be classified in the "endangered" category on the international red list of the World Conservation Organization in order to enable stronger protective measures. And the biologists demanded greater protection of the red thuns to secure the food base of the whales.

The Spanish government is only partially complying with these demands, such as the seasonal closure of the sea area where most orca-yacht interactions took place and the monitoring of Spanish fishermen.

López and other researchers emphasize: One should finally critically rethink the use of this sea area and the effects of human activities on the orcas and proceed against illegal fishing and activities.

Since 2020, the Spanish Coast Guard has been warning smaller boats about orca activities via radio. If orcas are spotted, for example, boatmen are asked not to approach and to give the animals enough free space. In the summer of 2020 and 2021, the Spanish authorities finally closed the sea area to small boats after too many yacht-whale encounters. To ensure that boaters can safely get through the waters and that the animals are not additionally endangered, the Iberian Orca scientists have developed a code of conduct for boaters.

One of the advice is to stop the boat and let go of the tax immediately. In addition, skipper should not shout or touch the animals and do not throw objects for them, but rather photograph them so that the marine scientists from Iberian Orca can then identify them. In addition, it is important to contact the Spanish and Portuguese authorities, by phone at 112 or via VHF channel 16.

One solution: cooperate with killer whales instead of competing

The authorities continue to observe the development. If necessary, you would impose security measures again, says Alfredo López. Meanwhile, the biologist observes the partly lurid reporting. Instead of fueling fear and writing "killer whales", it would make more sense to communicate factual information on how to deal with the stressed whales such as the code of conduct for boat operators. Another approach would be to use more resistant boats to protect the crews. Then people might no longer react panically during such encounters, but would experience them as a unique encounter, says López.

In addition, Ruth Esteban, Alfredo Lopez and other orca researchers write in the journal "Marine Mammals Science" that more research is needed to better understand the behavior of killer whales. In addition, it is necessary to develop a strategy so that the lake area can continue to be usable even for small boats.

Not only sailors, Fischer would also benefit from peaceful coexistence. Jörn Selling reports on observations of how Orcas near the coastal town of Zahara de Los Atunes circle tunfish with the help of the fishermen and add more tunfish whales and people.

Cooperation instead of competition is the keyword. To get involved with each other should enable peaceful coexistence of humans and marine mugs - then, however, the tunfish would still have a look.

Note. D. Red.: An earlier version of this article stated that the attack took place "1000 miles east of the Galapagos Islands". We have corrected this.*