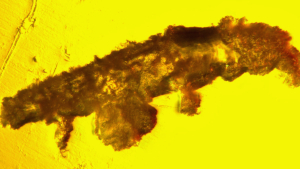

In the spring of 1822, a strange white stork near Klütz, a town between Lübeck and Wismar on the Baltic Sea, caused a sensation. On a "good thing belonging to Bothmer," later the "Freimümütige Abendblatt" reported, a stork appeared at that time, "with a thin stick over two foot, which hung down vertically and neither hung it down and neither in flying in his other movements seemed to be prevented, but from which the other storks by snapping and pull, although in vain, sought to free him. « For a few days or weeks, onlookers were able to marvel at the animal and ponder the nature of the 80 centimeter long stick on his neck, then puzzling had ended, as the newspaper noted: »He was finally to satisfy the general curiosity on May 21st d. J. shot there. "

The bird was killed by the landowner Christian Ludwig Reichsgraf von Bothmer (1773-1848), but as the sovereign of the state, the trophy was due to Grand Duke Friedrich Franz I of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1756-1837). The latter, an enlightened monarch and patron of the sciences, had the stork and the cane prepared in his own workshops under academic supervision and donated it to the Zoological Collection of the University of Rostock. There the doctor and botanist Heinrich Gustav Flörke (1764-1835) immediately set about the scientific investigation of the curiously injured and now stuffed bird. "The strange thing about this stork is a wooden arrow with a wide iron tip, which is stuck under the skin of the animal on the right side of the neck and protrudes far from the body at the bottom and top," said the professor of botany and natural history at the University of Rostock. "Since the iron tip is clamped at the top and attached to the end of the arrow with sinews, it can be concluded that a very distant winter quarters is where this stork received the shot.«

The arrow was also "made of very fine tropical wood," the botanist noted in his first report on the rector of his university in August 1822, but did not go into the probable place of origin of the floor.

A few weeks later, Flörke tried to answer a little more precisely in a more detailed contribution to the "Freimümütige Abendblatt", the question of the location of the winter quarters of the "poor Thiers": "Where he may have received the arrow, it can only be closed if

One canceled which wild peoples currently use such arrows. "He suspects that the stork would probably like to have been on the upper arms of the Nile."

«.

Not a man for sensational reports

The botanist, who also worked as a Lutheran pastor and who was to be positively acknowledged in an obituary as having "a rare humility and unpretentiousness" that "won the hearts of all those who were lucky enough to get to know him better", was not a man for sensational reports. His discovery was undoubtedly extraordinary. The Rostock arrow stork, as the bird is called after its place of storage, had literally carried the answer to an age-old question under its skin. "It was the first living proof of the long-distance migration of storks to equatorial Africa," emphasizes Ragnar Kinzelbach, Professor emeritus of biology and ecology at the University of Rostock, an outspoken connoisseur of the history of the arrow stork. "It is a milestone for a paradigm shift and for the gradual beginning of scientific bird migration research.«

Our primeval ancestors will have puzzled over the annual disappearance of individual bird species and their reappearance. Even the earliest known poets did not escape the seasonal spectacle, which the birds offered on their arrival and even more. Homer, for example, compared the deployment of the Greek warriors in front of Troy with "the birds flying", which gathered in Asia Masia, where they flew here and "flee and there, with a joyful vigor of the wings" -Year after year a late summer autumn natural spectacle on the Bosphorus, for example, on the Dardanelles or the coasts of today's Turkey. Herodotus (around 480–420 BC), who already knew how to report, also came from ibidendort. Swallows and storks hibernate in Egypt, according to the well -traveled historian and geographer, others would continue to move further. "The cranes leave when winter comes, the Skythenland and move to the source areas of the Nile."

When Aristotle erred

Apparently, the ancient Greeks already had some knowledge early on about the seasonal migration of birds. Somehow, but not either. Aristotle (384-322 BC), for example, suspected that some of the birds would hibernate – storks, for example, in the interior of hollow trees, and swallows at the bottom of swamps or lakes. Still other species of birds underwent a seasonal transformation process. According to the ancient philosopher and naturalist, garden redtails, for example, turned into robins over the winter and back to their original form in the spring. An obvious thought: while garden redtails, as we know today, are long-distance migrants and winter in Africa, robins from northern and eastern Europe spend the cold season on the Mediterranean – for example in Greece.

Storks prefer moist grass landscapes and probably also spread in the wake of humans. Where our ancestors roded forests to put on fields, they also liked to settle down and built their nests near human settlements or on the roofs of their houses. Since the birds hunt snakes and frogs, the animals were always welcome to the inhabitants of the houses. Due to their pronounced brood care, storks also considered the Greeks and Romans as role models for parental devotion in rearing as well as for the active gratitude of the boys who were assumed that they later took care of their then elderly - for example by They would take piggyback on the long journey to the south. For this piety towards its ancestors, the Roman author Aelian wrote around 200 AD in his work "De Natura Animalium" (from the essence of animals), citing an older, today lost work, the storks from the gods would rewarded that, even old, they hoe on oceanic islands to spend their retirement there as humans. In the Islamic culture, too, the stork was and is high reputation as Haji Laklak, who pilges to Mecca every year.

Unclear target

Many of the myths and legends surrounding the storks and their annual disappearance reveal, among many other things, that humanity already had a fundamental knowledge of the migration of birds very early on. "The departure was undisputed, but the destination was unclear," says the zoologist Kinzelbach. The bird-knowledgeable Staufer Emperor Frederick II (1194-1250) also reported about this in his work "De arte venandi cum avibus" (From the art of hunting with birds) and named the phenomenon with the term "transitus". His contemporary, the German scholar Albertus Magnus (Albert von Lauingen, c. 1200-1280), on the other hand, was of the opinion that storks wintered in swamps or caves.

In the early modern period, however, there was hardly any doubts about the bird train. Individual naturalists already had an idea where the journey of the birds went. The French doctor, botanist and traveling Pierre Bellon (1517–1564), for example, had personally observed and reported and reported on them in Egypt and the Levant moving storks and pelicans. Conrad Gessner (1516–1565), a Swiss doctor and natural history, was one of several authors of his era who found it worth capturing the history of the stork of Oberwesel for posterity, the lord of the house, on the roof he Nitled, a spring as well as a ginger root as a gift gift, should have put it from a distance - clearly a souvenir from foreign, overseas areas.

Despite the numerous indications, however, the knowledge about the migration of birds did not prevail permanently either among scholars or in the general public. Or it was lost again, "especially during the cultural upheaval in the Thirty Years' War," Kinzelbach suspects. New theories have been developed, new answers to the question of where the birds are disappearing to have been sought. The naturalist Charles Morton (1627-1698), author of the first English study on the subject, came up with a particularly original thought. He suspected that storks – as well as cranes and swallows – wintered on the moon. A month, Morton estimated, the birds would need for the distance between the Earth and their satellite. So it was quite a short trip, which they managed quite comfortably and mostly sleeping, thanks to the absence of air resistance and gravity. Carl von Linné (1707-1778) was not quite as far off as the Englishman, but even the Swedish founder of systematic biology was convinced that swallows would spend the winters in the mud at the bottom of lakes.

The last riddle of the white stork pull

With the arrow stork from the Baltic Sea, the question of the whereabouts of the birds in winter had not yet been completely clarified, but there was no longer any doubt about the long journey to Africa per se after May 1822, at least in professional circles. Meanwhile, the knowledge of the migration of birds has been part of primary education for decades, and the fact that the animals move to Africa in different ways is now known even to moderately interested laymen. But experts are still puzzling why, for example, some of the Central and northern European storks choose the western route via France, Spain and the Strait of Gibraltar for the up to 5000-kilometer journey to the wintering grounds on the Black Continent, and another chooses the eastern route via the Bosphorus, Asia Minor, the Levant and the Sinai.

So far, the bird researchers have also been inexplicable why even sibling birds choose different routes to Africa or why some storks move around the Mediterranean in one year, but the western route prefer the next. Another, but significantly smaller group of animals finally takes on the extremely arduous and extremely dangerous crossing of the Mediterranean from Sicily to North Africa. The flight over the open sea is life -threatening for the birds, since the air ther m as that rely on as a glider pilot.

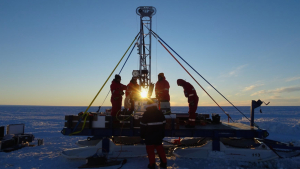

However, in the age of miniature transmitters, satellites and GPS, scientists are now able to locate animals to within a few meters, follow their movements and thus understand many of the individual decisions that individual storks make over the course of their lives, which can last up to about 35 years, and observe their consequences. And we are with you.

Thanks to the Animal Tracker app of the Max Planck Institute for Behavioral Biology in Radolfzell, for example, their around 300,000 users have been able to follow Alwins in recent months. The white stork female slipped in the spring of 2021 in Vorarlberg at the eastern end of the Lake Constance and had not chosen the West route to Africa like most of its conspecifics from this region, but for the monster tour along the Alps, along the Italian Coast to Sicily and from there decided over the open sea to Africa. On September 1, the animal landed safely on the island and in the weeks afterwards, several attempts to overcome the at least 150 kilometer route over the Mediterranean - in vain. Finally Alwin gave up and spent winter in Sicily. The stork apparently found connection there in spring 2022. Alwin has lived together with 19 fellow species between olive plantations and flowering meadows on the Mediterranean island and still made no move back to Lake Constance in mid -May.