From the window of a passenger plane flying over the Amazon, the view is breathtaking. "You see miles and miles of rivers and river islands," says Lukas Musher, a postdoc at Drexel University's Academy of Natural Sciences. The enormous river courses branch out like a dense, tree-like network that has formed again and again over the course of hundreds of thousands of years. New branches were added, old ones disappeared. The many flowing waters divide the forest into delimited spaces, each of which represents an independent world for the countless creatures that climb, crawl and fly here.

In a study published in 2022 in the specialist magazine "Science Advances" Musher and his co -authors report that the constant redesign of the rivers apparently inspired the birds of birds in the forests of the Amazon. The dynamic rivers act stronger than previously assumed as "species pump", which have made the Amazon forest one of the most species -rich places on the planet. Although the lowlands of the forest are only half a percent of the planet's land area, it houses about ten percent of all known species - and still still many strangers.

The idea that changing river courses can influence species formation in birds dates back to the 1960s. Nevertheless, most researchers have disregarded this phenomenon as the cause of the diversification of birds or mammals. "For a long time we considered the rivers as something static," says John Bates, a curator at the Field Museum in Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

Biologists have only recently started listening to the increasingly louder voices of geologists. "What the biologists brooded most was the realization of how dynamically the geologists assess the rivers," said Bates. He thinks a lot of the way the present work now combines biological data with geological ideas.

The relationship between geographical change and biological diversity is "one of the most controversial topics in evolutionary biology," admits Musher, who carried out the study as part of his doctoral thesis. Some researchers believe that the history of the earth has only a minor influence on the patterns of biological diversity, while others emerge from an extremely narrow, basically linear relationship between the two.

Excursion to the jungle

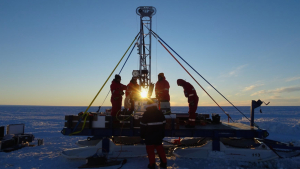

In order to examine the design influence of the currents on the birds in the Amazon area, Musher and his employees from the American Museum of Natural History and the Louisiana State University were under an expedition to the rivers that flow through the heart of Brazil. They collected examples of birds in several places on both sides of two rivers: the Aripuanã and the Roosevelt - named after Teddy Roosevelt, who traveled there as part of a mapping team in 1914. In addition, they got samples that had previously been collected by other institutions on other rivers in the Amazon area.

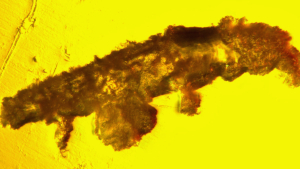

Scientists focused on six groups of species of birds, which, as a rule, do not fly very far. "If you want to know how the river affects birds, you also have to choose the birds that the river affects," Musher jokes. These species, including the blue-necked passerine bird (Galbula cyanicollis) and the drop-mantled antbird (Phlegopsis nigromaculata), spend most of their time in the undergrowth of the southern Amazon lowland. There they follow swarms of ants and eat insects that have been scared off by the ants.

The researchers sequenced the genes of the birds and compared them with each other. So they could see how they have changed over time. Then they relate the discovered changes in the genome to geological changes in those rivers in whose surroundings the birds lived and lived. As expected, the research group found that rivers for the birds represent barriers: If rivers branched off, populations were cut off from each other. Even relatively small rivers were able to separate populations and thus promote the differences in their genome. The scientists confirmed their results with a model that, based on the number of mutations, indicates a kind of how long it was separated from other peers.

Always on the move

However, they also noticed that the river courses are not static but dynamic barriers. Formerly shared rivers often combined again, so that the separate populations mixed up again. Sometimes the different populations were too different after a long period of separation to cross again. From then on there were separate species. As a rule, the birds used these reunits to replace newly acquired genes. This "gene flow" led to new gene combinations every time and has probably produced a variety of new bird species over time, explains Musher.

In fact, the diversification of the different species varied depending on how and in what period the rivers had changed. The researchers found that the geology in the west of the Amazon Basin caused a stronger gene flow between the bird species than in the east. In the western Amazon, the landscape is rather flat, and the rivers meander much more, because their banks erode more, which changes the course of the river. In the east, on the other hand, the landscape is very hilly. Here, flowing waters dig into the rock, which is why the riverbed is usually much more stable and less winding.

With the help of a mathematical model, the researchers were able to show that today's rivers as predictors for the genetic divergence are more decisive than environmental conditions and the spatial distance between the species. Changes in the river courses are therefore important so that a contact and therefore a gene flow take place, explains Musher. Probably other factors also play a role that the researchers have not taken into account - nevertheless, the results clarify that the dynamics of the earth and its biological diversity are sometimes inseparable.

Although at first it sounds illogical that rivers can restrict birds in their radius of movement. But it has been proven that a number of bird species do not fly over some flowing waters. "Even some of the relatively small rivers in the Amazon look like looking at a horizon from the perspective of a bird," explains Philip Stouffer, a professor of conservation biology at Louisiana State University who was not involved in the study. "For birds that don't usually travel long distances, this is simply an insurmountable hurdle.«

In addition, many birds that are adapted to life on the dark forest floor crossing not reluctant to cross -sunny. You have little motivation to leave your well -known habitat - the same applies to other animal species that live with the birds in the Amazon. It was also possible to show that the redesign of rivers is also very important for the diversification of aquatic organisms such as fish in the Amazon area. The same applies to other species such as primates and butterflies.

Birds are probably the best recorded group of living beings on our planet, but even from them "we can still learn something about the basic patterns of biological diversity," says Musher. According to him and his colleagues, similar geological processes probably influence - be it through changed river courses or other landscape changes - the local biodiversity elsewhere on Earth. It is quite possible, however, that it is a little different from in the Amazon area, because: "There is simply nothing comparable on earth."

© Quanta MagazineVon der Wissenschaft" translated and edited version of the article "Reshuffled Rivers Bolster the Amazon's Hyper-Biodiversity from "Quanta Magazine", a content-independent magazine of the Simons Foundation, which has set itself the goal of disseminating research results from mathematics and the natural sciences.