The pictures have become sadly famous: lonely fishing nets floating in the sea with dying or dead fish, sharks, marine mammals and seabirds tangled in them. These lost or deliberately discarded nets and fishlines get tangled into knots and often pick up other garbage floating in the water. After all, the balls of nets drift with the currents through the oceans and continue to catch marine animals in the process. The animals wriggling in the deadly meshes in turn attract hungry hunters, who then also get tangled. If the plastic webs sink to the ground, they can bury or damage entire communities such as coral reefs or seagrass meadows under them. Larger animals swallow power supplies whole, as the stomach contents of a sperm whale stranded on the North Sea coast in 2016 showed.

Spirit networks are a global problem in the oceans, the extent of which nobody can exactly quantify. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated in 2018 that 640,000 tons of lost or abandoned fishing nets come into the oceans annually, and in the European seas alone there are more than 1000 kilometers of networks a year. In the North and Baltic Sea, they often get involved in balls on the many shipwrecks and become death traps for numerous animals.

But with the spread of the dangerous networks, a movement of volunteers has also built up who are trying to recover them. Kai Wallasch is one of them. He reports on one of his recent missions: together with two colleagues, he wanted to recover ghost nets. The team is one of the 250 divers of the international GhostDiving organization. Wallasch reports that a round structure on the seabed could be seen in the murky North Sea water at a depth of 15 metres: the boiler of a wreck from the Second World War, on which ghost nets had become tangled.

The three experienced divers are a well -coordinated team: one keeps the heavy network taut so the second can cut it through it. This work is physically exhausting and not harmless, because the divers could get involved in mesh and linen. That is why the third monitors his colleagues and the time: Because of the strong tidal currents in the Cold North Sea, they only remain about 45 minutes.

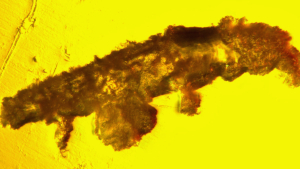

With a visibility of over two and a half meters, you would have been lucky on this dive, explains Kai Wallasch. However, the works often stir up mud, then they have to grope blindly with their hands. Bit by bit, they loosen the partially submerged and overgrown tissue in the seabed. If things are going well, the net can be cut into larger pieces of several meters. If the fishing tackle is reinforced with steel threads or lead lines, the bolt cutter is also used. Finally, they gather up loose threads lying around. Plastic nets always save them because of the microplastic problem, older nets made of natural materials sometimes leave them lying around: "A 50-year-old sisal net, which is populated by sea anemones, starfish and barnacles, already has a habitat character, we do not want to destroy such a community of life.«

After the dive, the stinking, wet plastic mesh must be disposed of with its metal, sediment and other contaminants.

Wallasch often takes the network home because the corresponding landfolves are usually closed at the weekend: If Fischer would report a lost network to the ghostdiving club, everything would be easier, according to the activist: Then the divers could recover it before it sinks into the sediment

Or harmonize.

Lack of control on the part of the legislator

Spirit laws not only endanger stocks and ecosystems, but are also a big problem for fishing. The European Union is trying to counter the risk of ghosts in European and international waters, explains Gerd Kraus, head of the Thünen Institute for Sea Fishery in Bremerhaven: »But a lack of control prevents an efficient implementation of guidelines; And the many, mostly regional projects with the aim of recovering lost networks, a common strategy has so far been missing. «

For example, fishing gear such as nets or longlines should be marked according to the EU directive and their loss would have to be reported immediately, but the control for this is difficult to implement: "If a German fisherman then also has to expect to bear high costs for the recovery of a lost net, the incentive to report the loss to the authorities is not very great." If the fisherman is afraid that he will have to bear the costs of disposal on land for randomly caught nets, then the motivation for this is also low. Most German fishing companies in the North and Baltic Seas are small family businesses and cannot bear such additional costs.

The NABU has built up an infrastructure for the simple and free disposal of old networks and other plastic waste in German ports in cooperation with fishermen and with financial support for the countries of Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein since 2011 in the FishingForlitter program.

"We also researched the causes of garbage," says Kim Detloff, the head of NABU sea protection.

About a third of shipping and fishing comes in the North Sea.

Some of them are contaminated sites, such as the large trawls from the earlier times of industrial fishing.

Today there are almost only small companies in the North and Baltic Sea that cannot afford the loss of a fishing dishes that cost several thousand euros.

"That is why fishermen try to rescue lost networks or with the help of colleagues." But repair items in particular are sometimes rinsed in the sea by high waves when the heavily stressed networks are repaired while driving on deck.

Even in smaller pieces of netting or lines, seals and seabirds can get tangled. They then often die slowly by starvation or from the injuries. Not ghost nets in the strict sense, but the so–called Dolly ropes are also a big problem in the North Sea: these short, frayed scouring threads made of polyethylene are woven in large quantities on the underside of nets – especially for the sole, but also for crab fishing - in order to protect the nets when they come into contact with the ground, because sand and pebbles constantly sand off fibers. Seabirds collect these fibers as nesting material, confuse them with food or get tangled in larger balls. As a result, more and more adult birds and chicks are dying in the Heligoland gannet colony, for example. That is why 70 percent of German fishermen are already voluntarily giving up on it, unlike, for example, their Dutch colleagues.

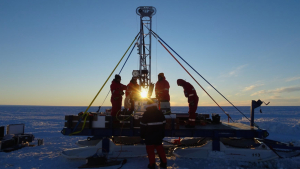

With sound waves on ghost hunt

The nets do not always snag on wrecks, some also simply sink to the bottom. Then the net search with divers becomes tedious and expensive. That's why the WWF has successfully tried out a more cost-effective method in its project "Recover ghost nets from the Baltic Sea": "With a sonar, we can check a 100-meter-wide strip on the seabed while driving over it once. Thanks to the high resolution, the echo of the sound waves directly shows us suspicious spots for nets and lines, then a diver can look there specifically," reports physicist and environmental scientist Andrea Stolte, who heads the WWF project. For example, the WWF has already recovered more than 24 tons of mesh netting from Sassnitz on Rügen alone.

Many of the spirits are repairs or contaminated sites from industrial fishing, some of them from GDR times: As now, nets from nylon were used. Since this plastic is heavier than water, such ghosts sink to the sea floor. Today in the German Baltic Sea, the stable network fishing is mostly particularly important through small family businesses. These have light plastic swimmers on the upper edge for the buoyancy and, to drop in the lower edge, small lead weight enclosed with polyester, explains Andrea Stolte. The thin filaments, which are upright in the water and usually firmly anchored, can be torn down by storm or careless boaters. Since they often remain upright as ghosts in the water near the ground, they can become death traps, especially for flatfish and diving seabirds.

The flying Dutch of the Baltic Sea

In the Baltic Sea, ghosts are caught primarily on the many wrecks or on ice-age rock deposits, explains the fishing biologist Thomas Richter, head of the fishing supervision in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. In doing so, they endanger the economically important recovery of the cod stock. Cods hide in caves between stones or in wrecks, they look for food there, then often get caught with the gills in the stitches of the spiritual networks and die.

That is why the WWF, together with cooperation partners, launched the project "Ghost networks in the Baltic Sea" in 2013. The experienced diver and geologist Wolf Wichmann has supported this mapping, documentation and partly also recovery of lost fishing equipment on a voluntary basis. He remembers his first dive to the "Flying Dutchman" off Sassnitz (Rügen) particularly well: on a dark March day at less than 13 degrees Water temperature, he saw the wreck wrapped in net fragments in the greenish dark water at a depth of 20 meters.

Since the net veil is reminiscent of tattered sails, divers jokingly call the wreck of the 20-meter-long sailor, sunk around 1900, the "Flying Dutchman". On such overcast days without sunshine, the visibility in the Baltic Sea is usually less than five meters due to algae and other suspended matter, in addition there is sediment swirled up during diving. Ghostnet fishing is not without danger, says Wichmann, you can quickly get tangled up with the equipment on the nets. Therefore, divers without appropriate training should not make their own recovery attempt, but report their sightings via the "ghost network app" of the WWF.

Since the Fischer family businesses of the Baltic Sea can hardly afford the loss of a 100 meter long network, they usually cover it themselves with GPS support. With their knowledge, many also help in the WWF project, the long-term ecological effects of network losses on the oceans Reduce and free the Baltic Sea from plastic waste. For their help in the costly rescue and disposal of the ghost network, fishing companies in the pilot project are given an allowance by the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. After all, the distance of garbage from the marine environment is a state task.

However, the net material mix of plastics and often also lead is then difficult to dispose of on land: contaminated plastic ends up in waste incineration, but lead must not be burned. "In Germany, after a long search, we found a waste disposal company that disassembles and separates the material by hand with great effort," explains Stolte. This means that the whole process is now covered in the project: from ghost net search by sonar to recovery by fishermen to disposal of the nets. The state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania has been supporting the pilot project since 2021; Schleswig-Holstein is also considering participating.

Time bomb marine plastic

But ghosts are not only an acute danger to sea creatures, but also a long -term one: the plastic filaments used in fishing since the 1960s rot extremely slowly. It can take up to 500 years, says Andrea Stolte. However, waves and currents grip these tissues between stones and sand into smaller pieces until they finally float invisibly in the sea as microparticles or deposit themselves in the sediment.

In plankton, the fish larvae then confuse the artificial particles with food, explains Gerd Kraus. The expert in the reproduction biology of fish looks at the effects of the microplastics on the fish stocks with concern: the indigestible plastic fills the stomach, reduces the growth and fitness of the fish larva or finally even lets it starve how studies from other sea areas have shown.

Through the food webs, microplastics also accumulate in larger animals such as crayfish or fish, which are part of the human diet. Since the harmful effect of plastic particles has already been proven for mussels, experts are also afraid of negative effects on human health. However, with the help of EU funds, something is already moving today, says Kraus. The European Maritime and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF) finances projects for more sustainability in fisheries, such as the installation of containers for the free acceptance of fished nets.

In addition, says Kim Detloff, you finally have to tackle the cause of the problem. For example, with a changed design, you could make fishing devices from a single or a few plastics and design so that they can be separated more easily later. That would enable more recycling and reduce follow -up costs. In any case, the problem of the ghost networks can only be solved together, all interviewees agree: by politics, nature conservation, administration, science and fishing.