The dry soil once lay under the roots of the trees and nourished the Chaco forest. These days she whirls through the settlement of Campo Loro in Paraguay, where the Ayoreo people live. Some of the indigenous people were abducted there decades ago. Like Mateo Sobode Chiqueno, chronicler of his people, grandfather and farmer. He sits in the semi-darkness of his wooden house covered with corrugated iron and runs a rag over his cassettes. There, too, the dust.

Since 1979, Chiqueno has been recording the memories of his compatriots with his tape recorder, the Paraguayan-Swiss director Arami Ullón Chiqueno has accompanied him for seven years for her documentary "Nothing but the Sun". The Ayoreo wants to know how old the people were when they first came into contact with whites, asks them about their beliefs and the old practices. He collects testimonies from another life in the forest. Testimony of his traumatic end.

The Gran Chaco is the largest coherent jungle area in South America after the Amazon. The forest extends estimated to be over 110 million hectares and covers large parts of today's state of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Paraguay between the Paraguay and Parana rivers and the Anden highland. It houses numerous animals and plants (see info box »The Gran Chaco«). Above all, the Gran Chaco is home to around 20 indigenous peoples. Many of them still live from what the forest gives for them. So also the last Ayoreo of the forest, the survival of which is in danger.

The Ayoreo were hunted, abducted and proselytized

Until about 60 years ago, numerous nomadic groups of the people roamed the extensive forest areas of chaco. The Ayoreo territory covered more than 32 million hectares until 1950, it stretched across the north of the Chaco from Paraguay to Bolivia - an area larger than Italy. Today the Ayoreo claim the land titles of 550,000 hectares of their country of origin. Today, 150,000 and 200,000 hectares in Paraguay are secured.

They followed the tracks of the anteater, hunted wild boars and dug up armadillos. The Ayoreo still know the bird that leads them to the honeycombs of the wild bee Cuteri, and they still know how to make textiles from the agave species Caraguata. But since the white people came, nothing has been the same in their lives.

In Paraguay, the members of the people were called "Moros" because of the darker skin color. Military and poachers hunted them like wild animals until the 1950s. Signs were hung in the chaco with the inscription: "Haga patria, mate un indio Moro" ("Kill a Moro Indian for the Fatherland"). They were considered dangerous, treacherous and bloodthirsty. The Ayoreo, for their part, called the whites "cojñone" – which means "those who do strange, senseless things".

The first Ayoreo to see the Paraguayan population was ten -year -old young José Iquebi Posoraja. He was captured in 1956 and brought to the capital Asunción in a cage. There they showed him around like a rare animal. “I said to them, I thought they would understand me. They took photos of me. I was afraid of the flashes, «says Iquebi in the documentary. "My grandfather said: 'It flashes with her weapons.' I felt very humiliated. People paid my kidnappers to look at me. "

After the government of Paraguay started looking for oil in its field in the 1950s, the vast majority of the Ayoreo was "contacted" between 1959 and 1987. This means that they were systematically tracked down, kidnapped and put into mission villages for re -education.

The gran chaco

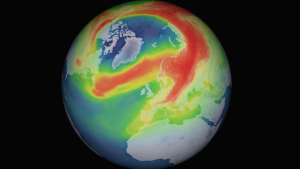

The Gran Chaco, or Chaco for short, in the interior of South America is considered the largest tropical dry forest on earth with a very rich ecological and cultural heritage. After the Amazon, the Chaco is the most important ecosystem in Latin America. With an estimated area of up to 110 million hectares, it covers Paraguay, Bolivia and Argentina. The climate is tropical to subtropical, which means: the summers are hot and humid, the winters moderately warm and sometimes very dry.

The three zones of the forest

There are different climatic conditions in the Chaco. The lower forest with its large rivers Paraná and Paraguay consists mainly of palm groves and is largely under water. The hilly landscape of the middle Chaco is used for agriculture, the high Chaco consists of dense, low dry forests. In Argentina, he is called the "impenetrable". There are still many cougars, tapirs and wild boars living there. There are also 150 species of mammals – including jaguars, tapirs, anteaters and capybaras. Twelve of them are not found anywhere else on Earth, like the Chaco peccary (Catagonus wagneri) and the small naked-tailed armadillo (Cabassous Chacoensis). Of the more than 3400 plant species that thrive there, 400 are found exclusively in the Chaco, so they are endemic.

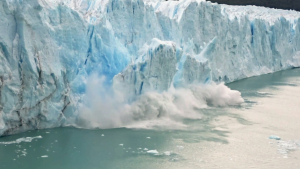

Intensive deforestation threatens large parts of the chaco

If the current destruction of the Chaco forest continues, about 70 percent of the untouched landscape will be lost forever by the year 2030, the Initiativa Amotocodie warned. Paraguay's Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development Ulises Lovera has signed an agreement according to which 30 percent of the Earth would like to be protected by nature by the year 2030. But even if this can be implemented, only 30 percent of the original virgin forest would still be standing in Paraguay.

At the end of the 1940s, the Salesian order settled in Asunción, then the fundamentalist evangelical missionaries of the New Tribes Mission and finally the Mennonites came.

They all wanted to "civilize" the indigenous people, as they called it.

For this, the New Tribes Mission used the traditional hostility of the local groups and organized expeditions with the already missionated Ayoreo to find isolated groups.

The missionaries were equipped with modern weapons with which they not only intimidated the Ayoreo, but massacred entire groups.

The government takes the Ayoreo their self-determination

In "nothing but the sun", Tune Picanerai remembers how he lost his wife: "The first encounter with the whites was fearing." While he speaks in front of the camera, he weighs forward and back again. He clamped an arch under his right shoulder. “After a curve there was a straight path ahead of us. Suddenly men appeared on horses. I said: 'We hide.' We fled into the forest to escape them. We ran as fast as we could. I noticed too late that we had taken different directions. We never saw each other again. Our fates separated. "

Mateo Chiqueno, his family and six other Ayoreo groups were brought to Maria Auxiliadora by missionaries in 1962. There, most of the abductees became infected with measles and died. Also Mateo's father. After six months, the survivors wanted to go back to the forest. But José Iquebi, who had been kidnapped himself as a ten-year-old, was one of the hunters at that time. He tracked down the escapees and dragged them back to the mission.

"I wanted to find my mother again," explains José today. He was happy to see Ayoreo again. "For me, a return to the forest would have been better," replies Mateo. “We died of their illnesses. I'm not angry with you, but our parents died of illnesses ... death came with them. "

Freedom was taken from Chiqueno, and even more was taken from him. "They took us to these inhospitable areas ruled by whites. Then they left us here alone. Then the cattle breeders came and took over our territory. They split it up, sold it and took everything away from us," says Chiqueno.

Around 5000 sedentary Ayoreo live in the edge of society. They sit on Kargem Land and try to wrest the ground corn, watermelons and sweet potatoes. Paraguay's government pays every family around 25 euros per month. For comparison: this corresponds to a sixth of the minimum wage that is paid in Paraguay.

It hurts to lose the country, says Chiqueno in one scene. However, even more severe weighed that the government deprives them of its self -determination. “We are no longer allowed to hunt, including the honey, the wild animals, they say. We even have to pay the water, «says the approximately 70-year-old. "The sun is probably the only thing that the whites do not yet call their own."

Untouched virgin forest is pushed over the heap

In the meantime, the country of the Ayoreo is one of the world's most sealed off. In such a short time, so much untouched jungle is literally pushed over the heap in such a short time. Paraguay has climbed into the league of the super pick -up, the country follows close to Brazil.

The large-scale clearing of the Paraguayan dry forest began at the end of the 1990s. More and more trees had to give way to more and more cattle farms. "It really took off in 2006 with the opening of the European markets for Paraguayan meat. It was previously closed due to foot-and-mouth disease," says activist Benno Glauser. Born in Switzerland, he has lived in Paraguay since 1977 and co-founded the Initiativa Amotocodie in 2002, which campaigns for the protection of the Ayoreo in the Chaco.

"Another thrust came with the soybean cultivation." The seed group Monsanto had developed a genetically modified type of seed, which also grew on the dry floors of the Chaco, continues Glauser. In 2009, 1000 hectares of forest were cut down a day. That means: An area was destroyed as large as the Central Park of New York every day. "Today the rate is somewhat lower, it is about 500 and 600 hectares a day - which is still catastrophic," says Glauser.

There is no end in sight. Because soy has become Paraguay's most important export product. The cultivation promises quick money for investors and drives land speculation: while one hectare of forest land in the Chaco could still be purchased for about 40 to 50 euros in 2008, the value increased sixfold in 2012, to about 240 to 300 euros. This is the result of a study by the Center for Development Research at the University of Bonn from 2021. In the meantime, forested land costs around 140 to 580 euros per hectare. Depending on the area, cleared pasture land is available for 500 to just under 2100 euros.

The trend is tempting. The soil prices not only attract domestic, but increasingly foreign investors who bet on rapidly rising returns in land shops. This in turn continues to advance the soymonocultures into forest areas.

The direct consequences of the deforestation boom are already noticeable for the forest and people: the droughts have become longer, storms have increased, and the groundwater level has decreased. This endangers the survival of certain plant and animal species, whose habitat is being contaminated by ever higher concentrations of pesticides and agrochemicals.

The forest is "Eami" and "Eami" is life

The land of the Chaco may be a profitable investment for land speculators and farmers. For the Ayoreo it is life, they call it "Eami". With air, water, plants and animals, eami is a living organism to which the Ayoreo belong. "It is a being with will, strength and potential," says ethnologist Volker von Bremen, who has been supporting the Ayoreo for more than 40 years.

"EAMI is necessary for the creation, preservation and further development of forces as a whole - from everything we would call terms such as nature, ecology and development in the holistic sense," explains von Bremen. "However, this perspective is completely ignored by those who seize the Ayoreo territory and exploit its natural resources."

Even though most of the Ayoreo have been robbed of their physical territory, Eami remains an important benchmark. "In addition to the material territory, Eami means a spiritual way of belonging and rooting," explains activist Benno Glauser. In this respect, the deforestation of the material territory would not affect the spiritual being at first, he goes on to say. This makes such cultures very long-lived, to a certain extent "persistent", as Glauser says. But he says: "Persistent, but not immortal.«

Contact means death

Since 1993, the Ayoreo have wanted to reclaim their land with legal means and protect their relatives who remained in the forest. In 2014, before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, they called for a halt to the deforestation of their last remaining forests and for their contribution to the sustainable development of the entire region to be recognized. According to observers, however, this is not very promising – the influence of those who want to clear the forest is too strong.

The members of the Bolivian and Paraguayan government know that Ayoreo is still native to the countries between the countries without contact with modern paraguayan society. Around ten family groups, around 150 people, live there in voluntary isolation and follow their old hiking routes. They are the last known indigenous groups - outside the Amazon area - that do not want contact with the outside world. Their routes are increasingly disturbed and interrupted by fences, streets and systems in the raw material industry.

In Paraguay, the members of Glauser's Initiativa Amotocodie observe how the isolated are doing. "Around the year 2000, new farms had sprung up on Ayoreo territory, exactly where we knew there lived a group without contact," says Benno Glauser. "We saw their tracks on trees, found their tools and footprints on waterholes and abandoned huts." For the sedentary Ayoreo it is clear: contact would mean death for their free-living relatives.

To protect them, the organization claims the country, which was originally populated by them: 10 million hectares. A small part of it, about 1.6 million hectares, are already protected as a national park. However, the rest is now considered a private property of various owners. Formally, the state would have to buy these areas back for the indigenous people. However, this is extremely unlikely.

An expressway could mean the end

In the near future, the Ruta Nacional PY15, a traffic corridor between the Atlantic and Pacific, Brazil's Atlantic port of Santos via Paraguayan territory, is to connect to the two Chilean ports Antofagasta and Iquique. It should not only strengthen the trade connections between Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, Chile and Bolivia, but will also combine the cattle and soy care with Asian markets. The first 275 kilometers of the flagship project of the Paraguayan government were inaugurated in February 2022. The remaining 256 kilometers are to follow by 2023.

The corridor not only threatens rare animals such as the large ant bears, which can only cross the expressway slowly, but is also a danger to the original inhabitants of these territories, said Miguel Lovera, director of the Amotocodie initiative to the »Guardian«. He strengthens the fatal pressure on the Ayoreo groups still living without contact. "This is the last nail in the coffin for the chaco and all of its peoples." This makes it impossible for the last indigenous indigenous indigenous are impossible to survive, Lovera fears.