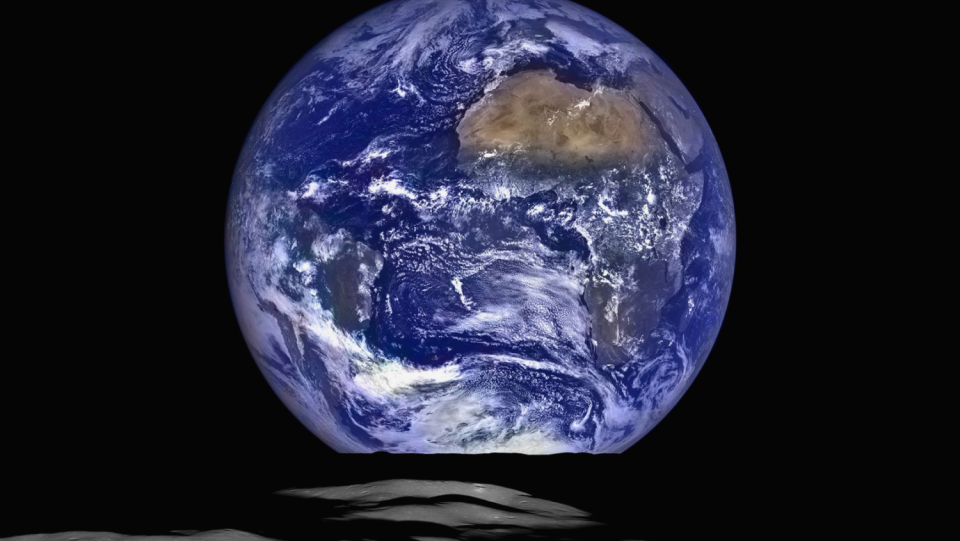

The Earth is not called a Blue Planet for nothing: it consists of far larger parts of water compared to other rocky planets, and oceans cover more than 70 percent of its surface. Where all the water on Earth actually comes from has been a hotly debated question among astronomers and geoscientists for a long time. Various theories are trying to answer them: it could be that the water was already contained in the building material when the Earth gradually assembled itself from smaller chunks in the early phase of formation; others thought that the building material was much too dry. Now a team of researchers is formulating another idea in the journal "Nature Astronomy": according to this, earthly water also comes at least a little from the Sun.

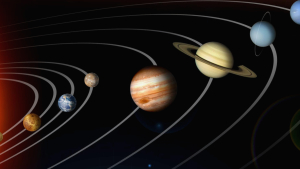

The team led by Michelle Thompson from Purdue University and Luke Daly from the University of Glasgow had searched for a possible source that has delivered water with the isotope ratio that suits the earth at some point in the course of the planet development. In the meantime, this source is suspected somewhere in the outer solar system: It would be conceivable that wet, so-called C-typnoids beyond the lanes of Saturn and Jupiter water dispensers: They are the origin of the meteorite class of the "carbon chondrite", especially primeval meteorites. The water of carbon chondrites has a reasonably suitable hydrogen isotope composition: The ratio of severe deuterium to normal light hydrogen corresponds roughly that of earthly water.

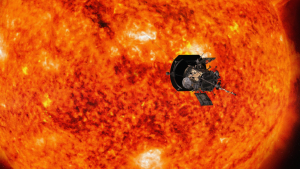

However, only approximately, not quite: Especially the water in the Earth's mantle, but also in the ocean, is somewhat lighter, so it contains less deuterium. In search of further evidence, Daly, Thompson and Co have now examined samples of the S-type asteroid Itokawa, which were collected by the Japanese probe Hayabusa and transported to Earth in 2010. The researchers focused on one question in particular: Could it be that the solar wind changes the asteroid's surface – and thus also the water reservoir of the rock?

In fact, this seems to be the case, as the analysis of the top 50 nanometer thick layer on the outside of the Itokawa dust crumbs shows. Above all, the dust here is quite wet: if the entire asteroid had a similar composition as here, then every cubic meter would carry 20 liters of water. The water molecules contain light hydrogen, no deuterium. Apparently, this water is formed in an astrochemical process over time, when the hydrogen atoms of the solar wind react with the oxygen from silicate rocks to form water, H2O and OH. This is also confirmed by experiments in the team's laboratory, where they fired protons at rocks and were then able to detect water molecules.

For the researchers, it is clear that this mechanism of water development in the solar system has a previously underestimated meaning: Water will be created wherever silicate rock is exposed to the sun wind. Also on the moon, for example. In the distant future, this could facilitate water supply from astronauts there or on other boulders. In any case, one should calculate the process if you want to narrow down the source of the water on earth: According to this, the light, which was created under sun wind bombardment, has mixed into the heavier mixture of the carbon chondrite. The water of the earth comes from several sources - and the sun has, as one of these sources, at least contributed hydrogen.