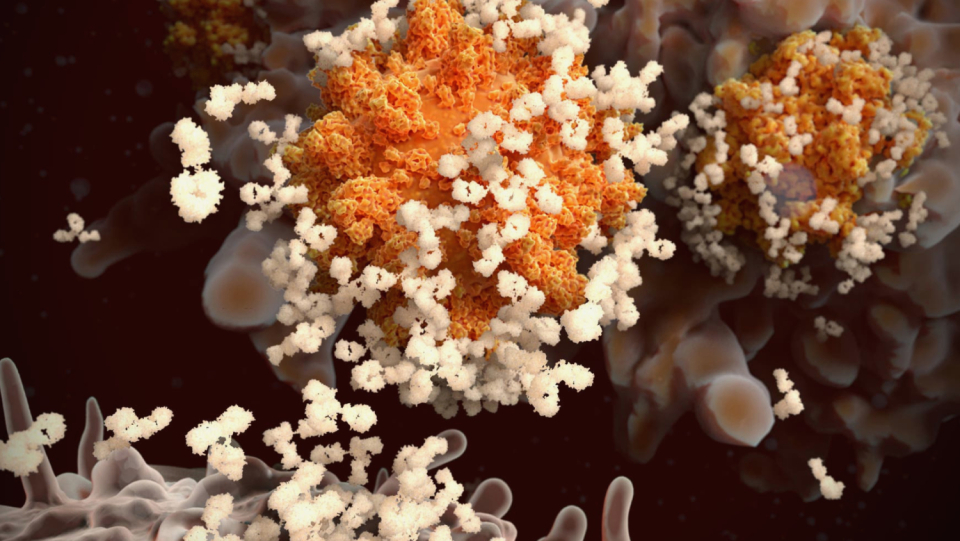

About a year ago-even before an expression such as "Delta variant" enriched the Covid 19 lexicon-virologists Theodora Hatziioannou and Paul Bieniaz from New York Rockefeller University built on a kind of Frankenstein variant of the Coronavirus. They made an important SARS-COV-2 protein, the spike protein, and began to change it so that it is no longer attacked by an antibodies that the human body currently offers for infection defense.

The spike protein is the key that the virus uses to gain access to cells. The aim of their research was to find out which components of the spike protein are actually attacked by the neutralizing antibodies. They built their research virus together from a pseudovirus that is unable to cause Covid illness and a colorful mix of gene mutations from the "worrying variants" circulating in the wild or found in laboratory experiments.

In a study published in the specialist magazine "Nature" in September this year, they reported that a spike mutant that contained 20 changes was completely resistant to all neutralizing antibodies that they let go of it. Or more precisely: against almost everyone. Because not even this artificially produced supervirus was immune to the antibodies of a certain group of people.

These were people who had contracted Sars-CoV-2 a few months before vaccination and had since recovered from Covid-19. The antibodies of these people even blocked completely different coronaviruses. "And it is very likely that they will work against any future variant of Sars-CoV-2," says Hatziioannou.

In a world that always looks anxious to new coronavirus variants, this "super immunity" has become one of the great puzzles of pandemic. Is it justified in the differences between immune protection after infection and immune protection after vaccination? And is there a safe and reliable path to cause such a superior body defense without prior infection? Finding answers to this is the hope of many experts.

"This plays into the question of booster shots and also how our immune system will be prepared for the next variant," says Mehul Suthar, a virologist at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. »At the moment we are flying blind here.«

The "hybrid immunity" is the secret.

The fact that newly vaccinated people who have already undergone a coronavirus infection develop an extraordinary immune reaction was shown shortly after the start of the global vaccination campaign. "We found that their antibodies reached astronomical levels far above what you can get with two doses of vaccine alone," says Rishi Goel, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia who is part of a team studying superimmunity — or "hybrid immunity," as most scientists call it.

Initial studies in people with hybrid immunity showed that their serum, i.e. the antibody containing the blood, was far better able to neutralize immune-weaking virus strains, such as the beta variant identified in South Africa, and other coronaviruses than with » Naive "vaccinated people who had never gone through an infection with Sars-Cov-2. It remained open whether this was only due to larger quantities or special properties of the neutralizing antibodies.

Recent studies suggest that hybrid immunity is due, at least in part, to so-called memory B cells of the immune system. The majority of the antibodies produced after infection or vaccination come from short-lived cells, the so-called plasma loads. They inevitably die and then the antibody levels also drop. Once the plasma loads are gone, the much rarer memory B cells, activated by either infection or vaccination, become the main source of antibodies.

Some of these long -lasting cells would form higher quality antibodies than the plasma loads, explains Michel Nussen branch, immunologist at the Rockefeller Institute. This is due to the fact that they develop in the lymph nodes. Mutations occur that help the antibodies to bind even more closely to the spike protein. When people who are recovered by Covid-19 are again exposed to this virus protein, these cells multiply and produce more of these highly effective antibodies.

"Then the whiff of an antigen, in this case an mRNA vaccine, is enough for these cells to literally explode," says Goel. In this way, a first dose of vaccine works for a person who has already been infected, just as a second dose works for someone who has never been infected with Covid-19.

Powerful antibodies do

In the memory B cells and their antibodies, it is probably also due to the fact that immunity after infection differs from that after vaccination. During infection and vaccination, the immune system is confronted with the spike protein in very different ways, explains Nussenzweig.

In a series of studies [1, 2, 3], his team, which also includes Hatziioannou and Bieniasz, compared the antibody responses of infected and vaccinated people. In both cases, B memory cells are formed, which in turn form improved antibodies by mutation. However, after an infection, this process seems to take place to a greater extent.

At the volunteers, the team isolated hundreds of B memory cells at different times after infection or vaccination. Each of them forms a unique antibody. But it turned out that the optimization of the antibodies continued for a year after an infection, while the process ended after a few weeks after a vaccination. B-memory cells that developed after the infection also formed antibodies against variants such as beta and delta with which the immune defense otherwise has more problems.

In another study, it was found that a past infection leads to antibodies that target more and different regions of the spike protein, thus binding it more evenly than antibodies after vaccination. People with hybrid immunity also produce higher and more stable antibody levels for up to seven months, reports a team led by immunologist Duane Wesemann of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

But not very shocking?

A problem of many studies on hybrid immunity: In most cases, the naïve vaccinators were not studied for very long. It is therefore possible that their B cells also produce more potent antibodies over time or after another dose of vaccine. At least that's what some experts suspect. It could take months for a stable pool of memory B cells to form and mature.

"It is not surprising that people who were infected and have now been vaccinated show a good reaction," says Ali Ellebedy, a B cell immunologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. "We compare someone here who started the race three to four months ago, with someone who has only now got into the race."

And so, in fact, there is evidence that double-vaccinated people who have never been infected are catching up. Ellebedy's team collected lymph node samples from mRNA-vaccinated individuals and found evidence that some of their memory B cells developed mutations up to twelve weeks after the second dose, allowing them to recognize various coronaviruses, including some that are more likely to cause harmless colds.

And Goel, his colleague John Werry from the University of Pennsylvania and other team members, discovered that the number of B memory cells seems to be increasing six months after the vaccination, even among those who were never infected. Her antibodies also got better to neutralize different variants. The antibody mirrors dropped even after vaccination. "But it is also the fact that you have a pool of high-quality B memorial cells that you protect if you ever come back into contact with this antigen," says Goel.

An additional dose could resemble hybrid immunity.

A third dose of vaccine could allow people, even though they have never been infected, to get the benefits of hybrid immunity, says Matthieu Mahévas, an immunologist at the Institut Necker-Enfants Malads in Paris. His team found that some of the B memory cells of naive vaccine recipients can recognize beta and delta two months after vaccination. "If you increase this pool with a refresher, you can imagine that you are creating strong neutralizing antibodies against the variants," says Mahévas.

To extend the interval between first and second vaccination could also imitate some aspects of hybrid immunity. An involuntary experiment provides indications for this: When the vaccine reserves became scarce in 2021 in the Canadian province of Quebec and the number of cases increase, the authorities recommended a distance of 16 weeks between the first and the second dose. In the meantime it has been reduced to eight weeks.

A team led by Andrés Finzi, a virologist at the University of Montreal, observed that people vaccinated under this extended schedule had similar Sars-CoV-2 antibody levels as those with hybrid immunity. Their antibodies were able to neutralize a number of Sars-CoV-2 variants – and even the virus responsible for the Sars epidemic from 2002 to 2004. "We are able to bring people who have not been infected to almost the same level as vaccinated people who were previously infected, which is our gold standard," says Finzi.

To better understand the hybrid immunity is the key for many scientists to be able to imitate them. Presumably not only the system of B cells has to be examined, as the latest studies did, but also that of the T cells. A real infection also triggers reactions against other viral proteins, not only against the spike protein, which is based on most vaccines. For Nussenzweig, this raises the question of whether there are also other factors that are also important in natural infection. For example, in the course of an infection in the airways, hundreds of millions of virus particles on immune cells, which also always get into the nearby lymph nodes, where B-memory cells mature. In some people, viral proteins remain in the intestine months after recovery. It is quite possible that this continued confrontation helps the B cells to refine their response to Sars-Cov-2.

According to the researchers, it is also important to check whether the benefits of hybrid immunity are not only evident in the laboratory, but also in reality. A study from Qatar suggests this. It found that people vaccinated after infection with Pfizer-BioNTech's mRNA vaccine are less likely to test positive for Covid-19 than people who haven't had an infection. According to Gonzalo Bello Bentancor, a virologist at Instituto Oswaldo Cruz in Rio de Janeiro, hybrid immunity could also be responsible for the decline in case numbers in South America. Many South American countries experienced very high infection rates at the beginning of the pandemic, but have now vaccinated a large proportion of their population. It's possible that hybrid immunity blocks transmission better than immunity from vaccination alone, says Bello Bentancor.

Since the vaccination breakdown caused by the DELTA variant are increasing, researchers such as Nussen branch now also want to examine the immune response of people who have become infected according to their COVID 19 vaccination and not before. When it comes to flu shot, the first encounter that someone had with a flu virus influences how the immune system reacts to future encounters and vaccinations. Research here speaks of the "antigens' sin". It would be interesting to find out whether she also appears at Sars-Cov-2.

However, researchers working on hybrid immunity warn against self-experiments. The risks of a Sars-CoV-2 infection are significantly higher than the benefits that could result from it for the immune defense. "We advise everyone not to risk infection and then get vaccinated just because the vaccine reaction might be better," says Finzi. "Because some of them wouldn't survive."

© Springer Nature 10.1038/D41586-02795-X, 2021