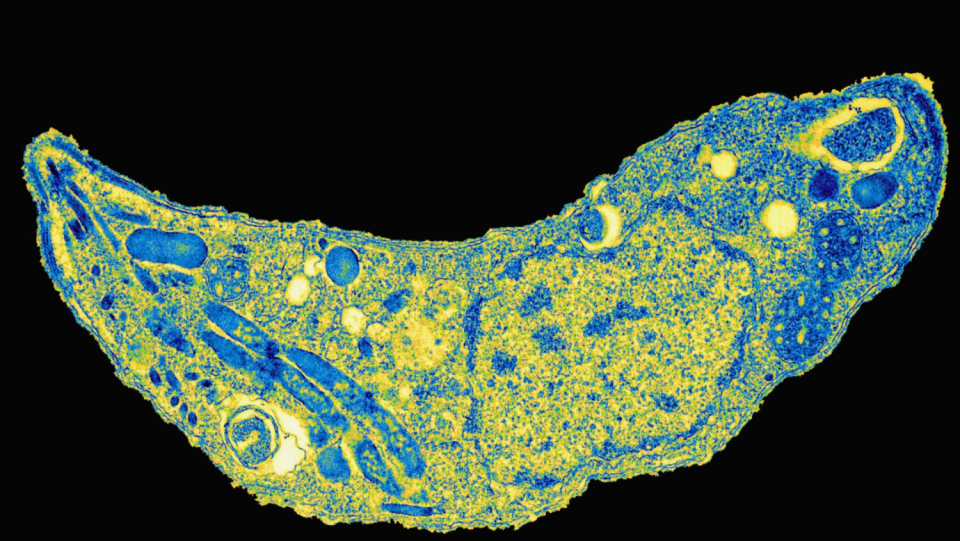

Let's make it short and painless: it's not unlikely that you have a parasite in your brain. It has inconspicuously entered your body and is now hiding in your nerve cells, among other things. The intruder, Toxoplasma gondii, is likely to be familiar to many parents – if pregnant women become infected, this poses a risk to the unborn child. An infection in the first trimester of pregnancy can cause a miscarriage or malformations. If it occurs later, it leads to consequential damage such as deafness or epilepsy in some children. The pathogen is also dangerous for people with immunodeficiency, such as AIDS.

In addition, the unicellular body can trigger a latent disease. Almost unnoticed, he penetrates into the central nervous system and then survives there for decades. Slowly there are evidence that even in this resting form it is anything but harmless. Presumably, he can even change the behavior, thinking and personality of his host permanently.

T. gondii is one of the most successful parasites worldwide. According to current estimates, almost one third of humanity carries the microorganism. In some regions of Africa it is up to 90 percent of the population, in Brazil 80 percent and in Germany around 50 percent. Most people do not even notice the infection. Only one in ten have non-specific symptoms such as mild fever, fatigue and headaches and body aches.

For the parasite toxoplasma gondii, people are only an intermediate host. He primarily occurs in cats that excrete his eggs over her feces.

In most cases, an infection remains symptom -free. However, the unicellular body can penetrate into the central nervous system and settle there.

According to some studies, T. gondii affects neural processes of the host. Sometimes it even contributes to the development of schizophrenia.

Man is an intermediate host for the parasite. T. Gondii primarily affects various cat species - only in them can he multiply gender and complete his life cycle. Stubnigeners divide parasite eggs for one to three weeks after the infection, some wild cats do this all their lives. As soon as they get into the environment, they mature, distribute their spores and thus contaminate water sources, soil and crops. In addition to humans, the parasites affect rodents, chickens, pigs and cattle. A further source of infection is not pierced of these animals. Here in the country there is probably even a large part of the infection back to the consumption of contaminated raw meat.

From the gastrointestinal tract, the parasite gets to our brain-even though the organ is protected from pathogens by the blood-brain barrier.

How T. Gondii succeeds is still unclear.

A theory is that he insert himself into the central nervous system inside of immune cells.

The infection makes them more flexible, and this sometimes enables them to wander through the endothelial layer of the protective barrier.

Once the parasites have reached the brain, they nest in neurons and glial cells.

Studies from deceased animals and humans have shown that they can occur in almost all brain regions.

Above all, they can be found in the Amygdala, the Thalamus, the Striatum, the Hippocampus, the Kleinbrank and in the cerebral cortex.

Apparently, T. gondii can manipulate its intermediate host in its favor. His goal: He should be eaten by a cat if possible. Experts have studied the mechanism extensively on rodents. Infected animals appear outwardly healthy and fit. However, they behave differently than their uninfected counterparts. A team led by Manuel Berdoy from the University of Oxford demonstrated the so-called Fatal Feline Attraction in rats in 2000. 23 laboratory rodents that had been infected with T. gondii (and had subsequently formed corresponding antibodies in the blood serum) showed no fear of the smell of cat urine. Some animals even seemed to be attracted by the scent. The 32 control animals behaved normally; they preferred those corners of a labyrinth where their own body odor prevailed. They stayed away from cat urine as much as possible. Both groups behaved the same with rabbit urine.

In other studies, scientists found that rats and mice with toxoplasmosis were more active than non -infected animals. They were also less afraid of new stimuli, reacted more slowly and preferred to stay in open terrain. All of these behaviors increase the likelihood that they fall victim to a cat.

In 2011, a working group around the parasitologist Jaroslav Flegr from Karls University Prague reported on a form of Fatal Feline Attraction in humans. The researchers kept 168 volunteers under the nose: urine of cats, horses, tigers, hyenas and dogs. On average, the 15 men tested positively for toxoplasmosis were more pleasant, but the 17 toxoplasmapositive women were more unpleasant. How the gender differences came about did not clear the work. It also left open whether parasite manipulated people or whether it was a side effect of the infection.

A leopard and a monkey

The behavioral biologist Clémence Poirotte from the Center d'Ecology Fonctionnelle et Evolutive in Montpellier was also interested in the Fatal Feline Attraction. With her team, she examined the phenomenon of our next relatives in the animal kingdom in 2016, the chimpanzees. The only predator is the Leopard. 9 monkeys that had been positively tested for T. Gondii approached the urine of the big cat in experiments much more often than their 24 non -infected conspecific. The effect failed to do urine samples from tigers and lions - in contrast to leopards, these occur in the natural habitat of the chimpanzees. Poirotte concluded that the Fatal Feline Attraction in humans could be an evolutionary remnant from a time when our ancestors were still hunted by relatives of the cat family.

There are now hundreds of scientific papers on the influence of T. gondii on human behavior and thinking. Nevertheless, the collected data hardly allow clear statements. Several factors complicate research. On the one hand, ethics prohibit deliberately infecting people with an untreatable parasite. Experts are therefore dependent on serological tests that show which test subjects have formed antibodies against T. gondii – i.e. have already become infected. They then compare the behavior of seropositive and seronegative people. Such experiments only provide correlations; no conclusions can be drawn about cause-and-effect relationships from the results. Furthermore, different working groups often come to contradictory conclusions. How and whether an infection makes itself felt seems to differ from person to person.

Some of the work found indications that latent toxoplasmosis slowed the facial expressions and gestures. Affected people also have more difficult to concentrate. The parasite could also influence certain personality traits, as a working group around Thomas Cook from Mercyhurst University in Erie showed in 2015. Seropositive women who took part in the examination were according to their own statement more aggressive than non -infected persons. Men, on the other hand, described themselves as an impulsive in comparison.

Results of a study published in 2019 indicate that infection with T. gondii makes you more risk-averse. Researchers led by Mieszko Olczak from the Medical University of Warsaw examined the brains of 97 men who had died at an average age of 49. 42 of the people had died as a result of particularly risky, unreasonable behaviour – most had caused a traffic accident. The researchers found parasite DNA more frequently in them than in those whose deaths were not related to daring actions. Based on their findings, the authors even recommended toxoplasmosis screenings for pilots, air traffic controllers and professional drivers.

In a recent study, Arjen Sutterland and his colleagues from the University of Amsterdam scored 24 work on the connection between T. Gondii and unnatural deaths. According to their analysis, up to 17 percent of traffic accidents and 10 percent of all attempts at suicide could go to the parasite account. However, the authors note that most work had not included the influence of living conditions. People from poorer households are more common through accident and suicide and at the same time infect themselves with T. Gondii. So it cannot be ruled out that it is bogus correlations.

A cause or an effect?

However, data from the Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango in Mexico speaks against this argument. They indicated a connection between work accidents and the amount of T.-Gondii antibodies in the blood-but only with weak people. The research team speculated that they suffered more from infection due to malnutrition.

However, the chicken-and-egg question arises here: does toxoplasmosis make you more susceptible to certain circumstances, or is it the other way around? Some criteria help to estimate this. Thus, a suspected connection should be biologically plausible, which is true for the influence of T. gondii on neuronal functions. The parasites act on the host brain in various ways – for example, by activating the immune system or changing the brain structure and the release of neurotransmitters. Similar processes occur in a number of neuropsychiatric diseases, which suggests that the parasite may also affect mental health.

Psychiatric parasitism

The first study on the subject appeared in 1953 and looked at an increased risk of schizophrenia as a result of the infection. In the meantime, numerous works underpin this connection. For example, people who carry T. gondii are almost three times as likely to develop the mental disorder. A projection by epidemiologist Gary Smith of the University of Pennsylvania attributes almost 21 percent of cases to the parasite. Whether cat owners are more frequently affected is controversially discussed.

The fact that the infection often precedes the onset of the disease speaks in favor of a causal relationship between schizophrenia and toxoplasmosis. This was demonstrated in 2008 by a team led by David Niebuhr from the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda with a long-term study. The extent of observed brain changes also indicates an influence of T. gondii. In 2012, researchers led by Jiri Horacek from Charles University in Prague compared MRI scans of 44 schizophrenics with those of 56 control subjects. In several regions, the former showed less gray matter. The 12 patients who had antibodies to toxoplasma in their blood had even more pronounced changes on average.

Toxoplasmosis, for example, affects the concentration of signal molecules in the brain. For example, it increases the dopamine level in the central nervous system. T. Gondii produces an enzyme called Tyrosinhydroxylase, which also affects the production of the neurotransmitter, and excretes it within the brain cysts created by it. In people with schizophrenia you can also find too much of the fabric in the central nervous system; During the treatment of psychotic symptoms, medication that inhibits the dopamine signal path are used. In addition, the infection lowers the concentration of serotonin and increases testosterone levels. Collections of the amino acid Kynurenin have demonstrated experts in the brain of toxoplasma-positive rodents as well as in those with schizophrenia. A metabolic product of this molecule prevents the neurotransmitter release from the synaptic gap.

In addition, there is indications of a connection to the bipolar disorder: In the case of those affected, a T. Gondii infection can be demonstrated above average, as João Luís Vieira Monteiro de Barros from College of Idaho 2017 found in one review. Some examinations indicate a possible causal context. Inflammatory reactions that occur as a result of the disease are suspected of causing the psychological symptoms to flare up. Activated immune cells in the brain can damage the organ and thus cause psychotic conditions or affective disorders.

A similar mechanism is suspected in depression. There are indications that inflammatory processes are involved in their development – various pathogens have already been targeted as possible triggers, such as chlamydia and herpes viruses. In 2019, a team led by Tooran Naye-ri Chegeni from the Toxoplasmosis Research Center in Iran analyzed the previously published studies on T. gondii, but found no significant association between the presence of depression and antibodies against the parasite in the blood serum.

Toxoplasmosis's neurological effects are unknown.

The microbial theory has also been studied for a long time in neurodegenerative diseases. Scientists who have investigated a possible connection between T. gondii and Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease have so far come to mixed conclusions. In 2019, a working group led by Masomeh Bayani from the Babol University of Medical Sciences in Iran re-evaluated and systematically summarized the existing studies on the topic. Although she found no evidence of a connection with Parkinson's, there were some indications of a connection with Alzheimer's. According to the study author, further research is needed in order to be able to make an unambiguous statement.

Whether and how strongly the parasite in the organism is noticeable depends on a complex interaction of several factors. Among other things, this includes the genetic equipment of the host. For example, variants of a gene called Disc1 contribute to the immune response against toxoplasmosis. At the same time, according to some scientific studies, they increase the risk of a number of mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia. The blood group also seems to be significant. Several research work suggests that rhesus factor protects positively against some effects of toxoplasmosis. In addition, the genotype of the parasite determines the fate of the host. Different tribes from T. Gondii differ in how sick they make. A team led by Jianchun Xiao from Johns Hopkins University Medical Center in Baltimore examined the blood serum of hundreds of pregnant women in 2009. The researchers found that only the child's risk of psychosis was significantly increased when infection with toxoplasma T.-Gondii-Type 1.

Meanwhile, disturbing evidence suggests that T. gondii could use epigenetic mechanisms to alter behaviour across generations, i.e. in the host and its offspring. Additional studies are needed to estimate the magnitude of such effects. So far, there are no effective therapies that help with T. gondii infection. Vaccines for humans or cats are also not in sight. That's why you can only give worried people without an increased risk of toxoplasmosis one (not quite serious) piece of advice at the moment: Keep your eyes open when buying a pet and stay away from the Mettwurst!