The village of Salyantar is located just 120 kilometers from Kathmandu, but the journey to it takes four and a half hours. Bad roads lead down and up steep slopes. The curves don't want to end. A ride like a carousel for Deena Shrestha. Pale, she sits on the back seat. "It's okay," she says. "We don't have time for a break." Suddenly she instructs the driver to stop. She pushes open the door of the SUV, staggers to the side of the road and vomits her breakfast into the slope.

Make the world better: 12 women, 12 ideas

BurdaForward is one of three German recipients of a scholarship for constructive journalism. As part of the international project "Solutions Journalism Accelerator", BurdaForward, together with the renowned reporting agency "Zeitenspiegel", is implementing 12 multimedia productions from September 2022 to August 2023, which can be viewed on the pages of "FOCUS Online", "Bunte.de ", "Chip.de " and be published. The series is called "Making the World a Better Place: 12 Women, 12 Ideas" and presents the work of women scientists from the Global South, who are researching solutions to major problems of humanity with their team. It is about the first six of the so-called "Sustainable Development Goals" of the UN: no poverty, no hunger, good health and well-being, good education, gender equality, clean water and sanitation. Selected texts appear at irregular intervals. The project was funded by the European Journalism Centre through the Solutions Journalism Accelerator. This fund is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The 40-year-old could be more comfortable. Still research in an air -conditioned laboratory in the Brazilian Ouro Preto, where she wrote her doctoral thesis in parasitology with Italian and Brazilian scholarships: the "brain drain", the leaving and staying away of the best minds, inhibits the development of poor nations. But Deena Shrestha decided to return to her homeland: »In Nepal I feel free and independent. And I can do something for people and the country. "

Not fatal, but mentally anguish

Shrestha is on the way into the mountains to visit a pilot project of her research institute in the village of Salyantar: for the first time, mosquitoes with standard and computer-assisted traps are caught in Nepal and examined for worm larvae. The study is intended to help combat the elephantiasis - an illness that mainly affects poorer people in developing countries.

Especially the lower extremities swell, in some cases so badly that they are reminiscent of the legs and feet of elephants. Around 15 million people worldwide are affected by the oedema caused by nematodes. In men, the scrotums can bloat, sometimes to the size of a mango, sometimes to the size of a basketball. According to the WHO, 25 million men suffer from it. "You don't die from the disease," says Shrestha. "But it leads to physical disabilities, to mental anguish, and it is an obstacle to the development of poor families and societies."

In the village of Salyantar, 39-year-old Bimala Upreti is also affected. Throughout the morning, she has been harvesting lentils with her husband Govind, the basis of the daily dhal. The husband carries the harvest to her yard. If bimala has to drag heavy loads, the pain becomes too great. Her right lower leg and foot are swollen. Govind makes milk tea for his wife and Deena Shrestha while Bimala tells.

Children get and work - not be sick

"When I was about 18 years old, I first felt a nodule on my thigh," says the farmer's wife. "Determined by the nematodes that settle in the lymph node," Shrestha surmised. "Then my lower leg swelled," Bimala Upreti continues. "I had fever and pain. And I was very afraid: What would my in-laws say? Would my husband leave me?"

Like almost all the girls in the village, Bimala got married early, at 17. Her husband was a few years older. An arranged marriage, like most. Traditionally, the bride goes to the groom's house and also lives there with the in-laws. In the patriarchal society, many daughters-in-law are only well-off when they give birth to boys. I want them to work and not get sick.

"But I have a good man," says Bimala Upreti. He took her to a hospital in Kathmandu. There the doctors did not find the cause of their suffering at first. "Usually the symptoms only break out for much older people," explains Shrestha. "After the worms were in the body for years and decades." After all, a doctor had the right idea. He took a blood sample from Bimala - at night: because the offspring of the adult worms in the lymph nodes, the microfilaria, make their way through the bloodstream at night because the mosquitoes they need for further development, mainly at twilight and Darkness are active.

If a mosquito bites an infected person, it also sucks up the microfilariae. The larvae need the insect as an intermediate host: from the mosquito intestine they migrate to the pectoral muscles and develop there further, then they move to the proboscis. If the mosquito bites a human again, the larva can penetrate a human again via this tiny wound, migrate to a lymph node, become an adult worm there – and produce microfilariae again.

There are drugs against the pathogens

In fact, the twitching threads could be seen in the blood smear of Bimala under the microscope.

The doctor made the diagnosis of "lymphatic filariosis" after an infestation with Wucheria Bancrofti.

The threadworms disturb the flow of the lymphatic fluid from the tissue, which is why it builds up in the lymphatic vessels.

In addition, the worms trigger an immune response of the body that leads to inflammation and swelling.

There are secondary infections from bacteria and mushrooms.

All of this contributes to the development of elephantiasis;

This is how the disease is called when the edema has developed.

"There are drugs that kill the larvae in the body," explains Deena Shrestha. In 2015, its discoverers were even awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine. "But elephantiasis cannot be cured. Once symptoms have developed, they cannot be completely reversed." Therefore, the doctor at Bimala Upreti was able to stop the disease and prevent a bad disfigurement. Nevertheless, she now has to go through life with a damaged foot.

"Would you have married your wife, too, if you had known that she was infected?", Shrestha asks the husband. Govind Upreti hesitates. Then he says: "A difficult question. Doesn't every groom want a healthy bride?" Her life would have been different, says Bimala Upreti: "I would have remained lonely. People would not have looked me in the face, but only saw my leg.«

»So much individual suffering!

Every case is one too much, because everyone would be avoidable, «says Shrestha.

120 million people are infected worldwide.

For a long time, hardly anyone was interested: the elephantiasis is one of the "neglected tropical diseases".

Neglected because it only affects the poor.

"It probably needs hundreds to thousands of stitches with infected mosquitoes until the worms can settle in the body," says Shrestha.

So people who live under unsanitary conditions are affected together with their cattle, without a sewage system, where the water is in puddles in which mosquitoes can develop.

WHO wanted to eradicate the disease by 2020 – not everywhere it worked

In 2000, the WHO called out its program to eliminate lymphatic filariosis with the help of »Mass Drug Administrations« (MDA). In endemic areas, the entire population should take tablets for five years in a row that can kill microfilaria in the body. The disease should be eradicated by 2020. This worked in some countries. There was also progress in Nepal. In individual districts, every fifth inhabitant had the parasites at the turn of the millennium - they usually did not notice it because many cases go as symptomless and there are no edema. Of the former 63 endemic districts, 48 are now considered free of filariosis.

But are the success stories true? Have the actions also reached remote hamlets and farms? Since Deena Shrestha founded the Centre for Health and Disease Studies of Nepal (CHDS) seven years ago with microbiologist friends, filariasis has become a central task of her Institute for Applied Research.

Funded by international and national donors, her team conducted studies in around 40 districts to determine whether the disease can still be transmitted despite the pill campaigns. First- and second-graders were subjected to systematic tests. The children are so young that they had not been given any pills. If antigens of the parasite are found in the blood of many children, this means that the transmission in the region has not yet been completely and safely stopped: "In some cases, the health authorities then had to repeat the tablet actions in hot spots.«

The causes, which is why the disease still exists, are diverse

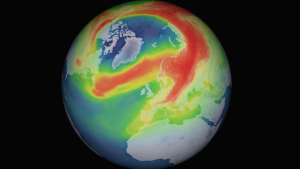

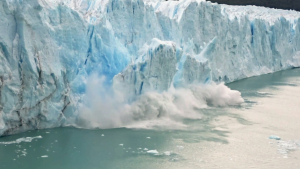

There are many reasons why the parasite has not yet been eliminated everywhere. Sometimes it occurs in areas where it was previously unknown, because the mosquitoes are advancing with climate change into ever higher regions. Many people are in India and the Gulf States as construction workers or domestic servants for months and years and are thus not reached by the pill campaigns. And there are many who doubt the medicine: some believe that the pills make men infertile, throwing away the tablets. Others want to avoid actual side effects: "Especially in infected people, the organism reacts, for example with fever or nausea, when the parasite dies in the body."

The problem with the antigen test is that it shows a positive result even some time after killing the parasite. The blood smears and the detection of microfilariae under the microscope are not practical for monitoring an entire region. "If we really want live assessments, it stands to reason that we should look at the broadcasters," Shrestha explains. That's why the pilot project with the mosquitoes is taking place in the village of Salyantar: "There are many cases of elephantiasis here, it's a good place to see if the tablet actions have actually interrupted the transmission or not.«

Traps attract the mosquitoes either with light or with an increased CO2 concentration – which prevails when people sleep. In the field laboratory in Salyantar, entomologists empty the traps every morning, identify the mosquito species under the stereoscope and preserve them for the trip to Kathmandu. There, the mosquito bodies are then examined for worm larvae DNA using PCR methodology.

The study is funded by Microsoft, among others, which is why, in addition to conventional trapping baskets, the company's new trap is also being tested in order to automatically determine mosquito species using the built-in sensor technology. The aim is to collect data over a year, how many mosquitoes there are over the months and if and when they are infectious. "These findings can then be used to optimize national and international programs to combat elephantiasis," explains Shrestha. "We have carried out antigen tests on the DNA of the parasite on the residents of Salyantar in advance. Some were positive. Therefore, I expect that the mosquitoes still carry worm larvae inside." But assumptions alone were not enough: "Only when we prove them, health programs will be improved.«

The use against the disease is also a struggle for justice, says Shrestha: "It is only a question of means and resources that decide on their elimination." If filaries occur in a family, she cements poverty.

Nepki Majhi, a woman in her sixties, lives on a remote courtyard.

When a secondary infection occurred on her leg affected by the elephantiasis, she had to be operated on.

In order to pay the treatment, her husband Budhi took out a loan from a local usurer, an interest rate of two percent per month.

To pay him off, he had to work for two years after Delhi, where he worked as a security guard seven days a week at night and as a car wash in the morning.

Bimala Upreti and her husband Govind were lucky that the disease was detected and treated early, so that her disability is not too severe. The spouses seem satisfied. On the street in front of her yard, a woman staggers past hunched low, with a huge bundle of grass on her back, which she carries with the help of a forehead strap. "With us, I carry all the burdens home, with joy," says Govind Upreti. "Because my wife does everything for me, too."

The project was financed by the European Journalism Center by the Solutions Journalism Accelerator. This fund is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.