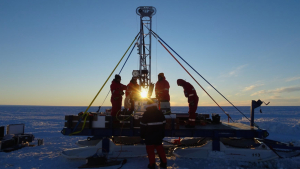

A Canadair-415 can absorb around 6000 liters of water within twelve seconds and throw it accurately over a fire. the EU purchased 13 of these propeller-driven firefighting aircraft from Canada in 2019 in response to the devastating forest fires, which caused more than 300 deaths across the EU in the previous two years. It will not have been the last bad forest fire season. Because of climate change, temperatures are rising, summers are getting longer, droughts are increasing – and with it the number of fires. The investment in fire fighting is therefore quite reasonable, but it has its price: a Canadair costs 30 to 40 million euros.

A goat, on the other hand, is already available for 100 euros, a beef or a horse depending on up to 1000 euros. Even an entire herd would be far from making millions. The herbivores cannot delete fires, but they may be able to prevent them. In any case, Guy Pe'er from the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research and the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research is convinced: "Great herbivores are able to significantly reduce the risk of fire in the landscape," says the ecologist. Pe'er is a co -author of the study "Effects of Large Herbivores on Fire Regimes and Wildfire Mitigation", which was published in the "Journal of Applied Ecology". Researchers from the University of Leipzig as well as the universities of Wagingen, Porto and Lisbon have investigated the question of what role large herbivores can play in fire prevention.

Use animals according to their food preferences

For their overview articles, the scientists have searched for studies that have dealt with the direct or indirect effects of herbivores on bush and forest fires. The result speaks for itself: 13 out of 21 studies and thus almost 62 percent came to the conclusion that grazing animals basically reduce the risk of fire. Most of the other studies also emphasize the positive effect of herbivores, but depending on the concrete conditions on site: whether it is really rarely burning depends on the season, the existing vegetation and the management of grazing.

"It's all about reducing the existing plant biomass," says Guy Pe'er. The fewer dry grasses or woody plants there are, the lower the chance that they will catch fire. The prerequisite for this is that the animals are also used according to their food preferences. Cattle, for example, are less suitable for bushland. Their stomachs do not tolerate herbaceous plants. So where trees and shrubs are to be nipped in the bud, goats and sheep are the better choice. That's because they also eat twigs, young trees, and bark. Cattle and horses, on the other hand, prefer to eat grasses (see info box). "It is usually most effective when different herbivores with different food spectra are used," says Pe'er.

Which animal eats what?

Goats are ideally suited for reopening dry sites that are in danger of becoming overgrown. They cover a higher proportion of their feed requirements than other grazing animals through leaves, bark and woody shoots (on average about 60 percent, and even more in winter). Goats eat shrubs up to a height of two meters, thin trunks are pressed down, and they also do not disdain thorny shrubs such as blackthorn, hawthorn and roses or coniferous trees such as pines.

Cattle get along well in dry and damp habitats. Your food includes grasses, herbaceous plants and trees. However, cattle are often not sufficiently contained by cattle. The combination of cattle with other animal species such as goats is therefore ideal.

Horses eat more selectively than cattle and focus more on grasses. They prefer nutrient -rich, young feed plants, but also eat fiber -rich, older greenery. Horses are not reduced very effectively by horses, but can be slowed down in all year round grazing. Horses are particularly suitable for habitats in which a certain floor opening is desired - because they roll on the floor or scratch their hooves. The areas are important for the germination of many specialized plants.

Over the centuries, sheep have contributed to the creation of grasslands, heathlands and sandy habitats. Many of these habitats, which are among the most species-rich in Central Europe, can therefore be best preserved if this extensive grazing is preserved by moving flocks of sheep. Woody plants are rather scorned by sheep, in contrast to goats, they can therefore also be used to graze orchards. Sheep have a much more selective way of eating than cattle or horses – they prefer young feed and avoid older and harder grasses.

Wisters come from without human care and creation and can therefore be used well in regions in which agricultural use has been abandoned. Wisent resembles the beef from the eating habits, but are somewhat better adapted to the digestion of woody food. Studies on the choice of food showed a maximum of 30 percent of a wooden content, especially in winter. In summer, their food consists mostly of grasses and herbs. Wisters are able to contain the amount of wood. Trees up to ten centimeters thick are compressed or stepped down during the change of fur.

If you let different animal species graze an area, mosaic-like landscapes form over time. The animals use certain areas and avoid others, so that a landscape is created in which forests, woody islands and open areas alternate. Fires can still occur there. But they can not spread as devastatingly as in a monoculture or an area covered with bushes.

The study is part of the Grazelife project, which was created on behalf of the EU Commission and should evaluate different forms of grazing whether they prevent fires, contribute to climate adaptation and increase biodiversity. "Fire management in Europe should focus much more on fire prevention," says Pe'er. So far, politics has invested primarily in fire fighting, i.e. in expensive fire -fighting aircraft and other fire engineering. "However, there is strong evidence that this policy of fire suppression leads to more flammable biomass and more intensive and more common fire in the long term." This development is reinforced by the widespread reforestation and the conversion of structural forests in monocultures, criticizes the scientist.

In order to really benefit from the positive effects of grazing animals, EU funding policy would have to be adapted in the future. In the "Common Agricultural Policy" newly adopted by the member states in 2021, there is still an area premium. This means that a farmer receives a defined amount of money for each hectare – regardless of how he cultivates the area. For small, traditionally working farms with grazing animals, this is a real disadvantage: because their areas are small, they get little money. For many farms and shepherds, working with the animals hardly pays off.

This is why the rural exodus continues, especially in regions in the Mediterranean, where the risk of fire is particularly large. According to the EU calculations, a total of five million hectares of agricultural area could be abandoned by 2030. The risk is at least increased for a total of 56 million hectares (30 percent of the agricultural area). The ecologically valuable, heterogeneous farming areas are particularly at risk. The risk that the areas will come on fire - already folded down by climate change - is further increasing.

Opening up prospects for rural areas again

"A paradigm shift in the funding - away from the area bonus, towards a kind of common good bonus would be necessary," says Guy Pe'er. If the farmers and shepherds were paid appropriately for the services they provided in the field of fire prevention and biodiversity, the rural exodus could also be slowed down. In any case, rural regions would get a perspective again in this way.

"It would also be an important step to open up forest areas for grazing," says Pe'er. So far, there are EU premiums for, among other things, the management of grassland, but not for forest. Grazing of forest areas would be ecologically and economically quite sensible. Even in the forest, grazing animals can significantly reduce the undergrowth and thus the risk of fire. In this way, a more open, park-like landscape can be created, which is much richer in species than a dense, closed forest.

Another sensible measure can be to make large herbivores such as horses or bison. "In areas where the country's management has already been given up, wild or half -winds could help prevent fires," says Pe'er. The corresponding funding opportunities would also have to be created for this. The animals could help stabilize a region again: a landscape that wisent or wild horses roam, for example, is interesting for ecotourism.

All considerations about grazing animals are not about transferring valuable arable land to extensive pastures. We are simply looking for ways to preserve as many of the small, sustainably working, agricultural enterprises as possible. And with them the many positive aspects that come with such land use.

In any case, this will only succeed if the European Union finally recognizes services that are beyond the immediate economic added value. It is not easy. A newly purchased extinguishing aircraft is a specific promise: capacity of 6000 liters, pumped out in just twelve seconds, a range of more than 2000 kilometers. A cow, on the other hand, is just a cow, a goat is a goat. Even if they come across the tall grass, you only see animals that eat - and no fire fighters.

Nevertheless, it could work with the method that seems a little archaic: pasture animals have a long tradition in the rural regions in Spain and Portugal, Greece, Italy and Croatia. They are firmly anchored in local cultures. So it should not be too difficult to bring more animals into the regions at risk. The EU would only have to make the funding a little more attractive. With the equivalent of only one extinguishing aircraft, many hectares of forest and bushland were saved from destruction.