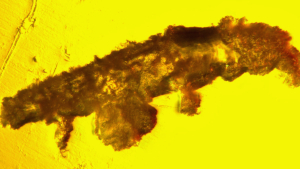

An adult quetzalcoatlus almost reached the dimensions of a small aircraft: its twelve-meter wingspan made it one of the largest airworthy animals on Earth that have ever lived. But these dimensions raised some questions that Kevin Padian of the University of California at Berkeley and his team could have clarified thanks to new fossil analyses, as they write in the "Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology". It was unclear, for example, how the pterosaurs could even rise into the air or what and how they ate.

The animals were a model of success: they lived on earth 150 million years until they suddenly died out with the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous season. And while in the sky they were like Albatrosse or vultures thanks to their enormous wings, they must have had considerable difficulties on the ground because of their long head and neck and the short hind legs to keep their balance and move. Compared to the feet, the wing bones were very long, from which Padian's working group concludes that the wings touched the ground while standing. Quetzalcoatlus and other large pterosaurs were probably like four -legged friends and supported the front extremities.

However, the giant could not walk with it, as the examination of the shoulder bones indicates: A bone on the shoulder joint prevented the pterosaurs from swinging their wings forward to walk. Instead, they had to alternately raise the wings left and right in order to be able to put the respective hind legs forward. Then they turned down the grand piano again to repeat the whole thing with the other side. This would also fit with tracks found in France in the 1990s and attributed to pterosaurs. Similarly, vampire bats move when they are on the ground.

Taking off was also made more difficult by this anatomy, which is why many paleontologists assumed that the animals fell off cliffs in a similar way to albatrosses. The updrafts on the rocks would then have ensured that the animals could sail. From the ground, on the other hand, it seemed an impossibility: due to the low fuselage height above the ground and the length of the wings, hitting did not bring enough lift. However, other theses assumed that the pterosaurs catapulted into the air.

As Reihier, for example, Quetzalcoatlus joined strong hind legs when he wanted to fly. However, it would also be possible that he fell off with all fours. He could then hit his wings above the ground; He had developed a very pronounced sternum where strong flight muscles started. Large bone combers also speak for this on the upper arms, which served as further anchoring the flight muscles. Once in the air, the Pterosaurs then used the thermal to slide over longer distances. The landing was more like that of birds of prey, which brake heavily with rapid wing strokes before they put on.

However, this considerable body also wanted to be fed: Padian and Co rule out the fact that Quetzalcoatlus ate carrion, as well as the fact that he took fish out of the water in flight. Against the former would speak the long and thin, but weak jaw anatomy, against the other the high energy expenditure of this type of hunting. It is more likely that the animals again waded through meadows or swamps like herons or storks to hunt lizards, fish or amphibians. The head and neck could be pointed vertically upwards to swallow the prey.

Not all the mysteries about these giants have been solved yet, but the study represents a major step forward. "The results are revolutionary for pterosaur research," says Padian.