In Bethesda, Maryland, 30 healthy people prepared for pain. Researchers at the US National Institutes of Health performed a biopsy: They punched three millimeters deep circular material out of the inside of the cheeks of the participants. In addition, they took a skin sample just below the armpit. Some time later, the scientists looked at the wounds on the cheeks and skin again. The difference between the two injured areas was remarkable: the sores in the mouth had closed within a few days. The cuts on the arm, on the other hand, still persisted after two weeks.

The results of the experiments, which were published in 2018, were not unexpected. It is no secret that the oral mucosa heals faster than the skin on the trunk and extremities. "If you cut yourself in the skin, it takes over a week for the cut to heal, " says the head of the experiment, Maria Morasso. The biologist works at the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases in Bethesda. "If you bite your cheek, it may hurt quite a bit, but the next day you won't find the injury anymore." In the oral cavity, quick repairs are certainly an advantage: on the one hand, injuries could be further irritated by chewing movements. On the other hand, the numerous bacteria and microbes found in the oral cavity thrive splendidly in the mucosal cracks.

Nevertheless, the Bethesda study made sense: the researchers hope to get closer to the secret of the healing powers of the mouth. Knowing the extraordinary wound healing could help doctors heal chronic wounds. Even the undesirable effects that the normal healing process of the skin brings could be stopped.

Sometimes injured skin heals too slowly or no longer. Such chronic wounds represent an enormous burden on the health systems: In the United States alone, an estimated 6.5 million people are affected. The risk of chronic wounds increases with age. Diabetes and obesity also make wound healing disorders more likely. The treatment of chronic wounds often presents doctors with a challenge-one that is only bigger in an aging population with more and more common type 2 diabetes.

Series: Mouth-friendly

Whether talking, eating, smiling or kissing: our mouth is almost constantly in motion. However, many people only notice how important it is that he stays healthy when the first aches and pains become noticeable, such as caries, gingivitis or nasty canker sores. Oral and dental care can have far–reaching consequences for the entire body - it is now even associated with diseases such as Alzheimer's, heart disease and Covid-19. You can find out what optimal oral hygiene looks like, what contribution the oral microbiome makes and what makes the oral mucosa so special in our series "Healthy in the mouth":

How scars arise

The injury does not always heal without a trace. Almost everyone has a scar somewhere. Some scars are harmless, others cause problems for their wearers: Scars that have arisen after major surgery or severe burns on a particularly visible part of the body such as the face can stigmatize those affected. Pronounced scars can also limit the function of the affected part of the body.

According to Phil Stephens, the fact that injuries in the mouth usually do not leave scars has an evolutionary reason. "If you are a cave person with a large wound on your arm, it will certainly leave a scar," says the cell biologist from Cardiff University. "But if the scar is in your mouth and you cannot eat - then it is over with you." He explains that connective tissue cells, so -called fibroblasts, drive healing by storing supporting tissue material into the wound bed. However, the cells sloppy into the skin - instead of healed skin, scar tissue remains. In the mouth, on the other hand, the cells incorporate their support material accurately into the surrounding tissue. The injury heals scars -free.

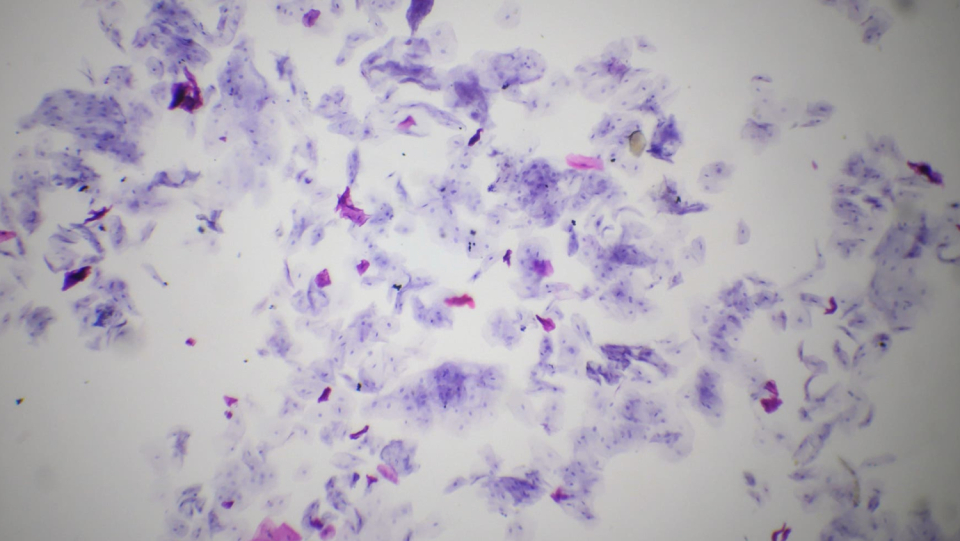

Specialists initially assumed that the superior healing ability of the oral cavity must have something to do with its specific milieu. Some suspected that the saliva could promote the healing process of the oral mucosa. Probably, the growth factors present in saliva still play a role in wound healing, says Luisa DiPietro, professor of dentistry at the University of Illinois at Chicago. In the meantime, however, science is increasingly focusing on the peculiarities of the oral mucosa cells. Since the mid-1990s, it has been known that cells from the oral cavity behave differently from skin cells. This is also supported by genetic analyses that have been carried out in recent years. "Under the microscope, the cells of the skin and the oral mucosa look very similar, but genetically they are really different, " says DiPietro.

Sometimes the oral caves healing forces also reach their limits. In fact, Dipietro has a small scar on the inside of her cheek - the remnant of a bicycle accident in teenage age, in which she was knocked out several teeth. "If you have considerable damage, everything is possible," she says. Nevertheless, it is fascinated by the mechanisms that control the almost perfect regeneration. Her research group discovered that inflammatory reactions take place in the mouth of the mouth than in the skin. Although inflammation is essential for healing - macrophages, the food cells of the immune system, crushed cells and divorce molecules that promote the tissue repair - according to Dipietro, they usually take over in the skin. »That may be a kind of insurance against infections. However, it goes at the expense of a certain tissue damage. "

Her research group also found that sores in the mouth and skin differ in their blood supply. If the body is wounded, blood vessels form to supply the injured tissue with oxygen and other nutrients. This process is called angiogenesis. The scientists around DiPietro found that after injuries in the oral cavity comparatively fewer blood vessels formed, but they matured faster. In the skin, on the other hand, many vessels quickly developed – but these were not so functional. As in the case of inflammation, angiogenesis in the skin after an injury seems to be too enthusiastic, says DiPietro. As a result, the rapid formation of new blood vessels even slows down the wound healing of the skin.

Enduring youth

In Bethesda, the biologist Morasso and her team carried out genetic analyses of the tissue samples of their test subjects. The results amazed them: After the skin injury, the genes SOX2 and PITX, which are responsible for the repairs, were activated. They were already active in the oral mucosa before the injury – and were present in greater numbers. According to the results, the oral mucosa is apparently ready to regenerate quickly at any time. "At the molecular level, oral tissue seems to be designed to heal," says Morasso.

According to molecular biologist Tanya Shaw of King's College London, all these differences could be due to the respective embryonic origin of the skin and the oral mucosa. The tissue of the oral cavity is derived from embryonic cells, which are called the neural crest. In contrast, the connective tissue cells under the skin surface arise from another tissue, the mesoderm. "There is some evidence that the neural crest cells are less reactive, so they may be dampening the inflammatory response," Shaw says. The similarities between the oral mucosa and embryonic tissue, which also heals quickly and without scarring, can hardly be denied. They suggest a possible "anti-aging mechanism" in the mouth.

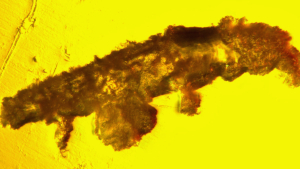

So could the oral cavity be a youth fountain? More than a decade ago, cell biologist Stephens and his colleagues compared skin and oral mucosa cells of the same patient. They found that the tissue in the mouth was actually younger molecularly biologically. In the mucous membrane cells, the chromosome ends, the telomeres, were longer than in the skin cells. Telomeres consist of repeating DNA sequences that do not encode for certain genes and become a little shorter with every cell division.

A short time later, the scientists from Cardiff provided a possible explanation for their discovery. Among the numerous cells of the oral mucosa there are not only mucosal cells, but also their progenitor cells - stem cell derivatives, from which several types of tissue can emerge. These cells are not only eternally young, but also have a strong immunosuppressive and antibacterial effect, says Stephens. Thus, they could also contribute to the extraordinary wound healing of the oral cavity.

Medications may prevent scarring.

The growing understanding of the healing abilities of the oral cavity paves the way for new treatment options. Adjusted anti-Anngiogenesis drugs that counteract vascular formation in cancer patients could prevent scarring after operations. In addition, medication would be conceivable that activate the repair genes. Morasso pursued this approach in an experiment with mice: animals that overexpressed the gene SOX2 in their skin cells actually healed faster than such without a gene surplus.

Stephens is skeptical about skin therapies that only intervene in a signal pathway of wound healing. This approach has proven to be treacherous in the past: ten years ago, researchers at the University of Manchester had pinned their hopes on the preparation they had developed, Avotermin – a genetically engineered growth factor (TGF-β3). In animal experiments, Avotermin had successfully accelerated wound healing, and initial studies in humans also looked promising. However, in the phase III study, the drug was not able to reduce scarring compared to a placebo. After the study results were announced in February 2011, the shares of the pharmaceutical company involved plunged.

So far, why the therapy failed has remained unclear. The TGF-β signal path, on which the avotor appointment has been scheduled, provides demonstration of wound healing. Stephens believes, however, that the scarring alone cannot be stopped by this path. "If you only pursue a single molecule, it is very unlikely that the approach will work," says Stephens. "Then there will be a balance through another molecule or another signal path."

Instead, he suggests treating scars or chronic wounds with a number of molecules that also speed up wound healing in the oral cavity. It would be possible to apply oral mucosal cells directly to the injured tissue. However, it would be very likely that the body would reject the foreign cells. In addition, such cell therapy is always associated with high costs.

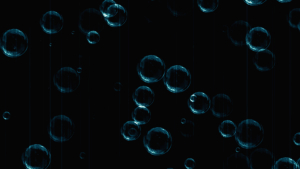

That's why you should not use the cells themselves, but the substances they secrete, explains Stephens. His team in Cardiff observed that tiny vesicles, the exosomes, could contribute to the wound healing process. The small particles are secreted by the stem cells of the oral mucosa and serve, among other things, to repel microbes. Also in the results of scientists from the University of Pennsylvania, the exosomes appear. Exosome-containing drugs, Stephens hopes, could reduce scarring, accelerate the healing of chronic wounds and prevent wound infections. However, before such a preparation can be tested on humans, it must first prove to be effective in animal models – ideally on pigs whose skin resembles that of humans.

Clinically approved skin therapies, which are based on wound healing in the mouth, may be a further thought. However, Dipietro is enthusiastic about how many scientists are already devoting themselves to the research area. It not only hopes for therapy options that make wound healing possible without scarring, but also dreams of being able to renew defective skin areas quickly. Similar to a salamander that his limbs grow back. "The oral mucosa has great hope that people are capable of healing themselves regeneratively," she says. "I think she could really be the key."

This article is part of Nature Outlook: Oral health, an editorially independent supplement produced with financial support from third parties.

© 📓 🐠 📬 : 👄 🏥 , 1⃣ 0⃣ . 1⃣ 0⃣ 3⃣ 8⃣ /d 4⃣ 1⃣ 5⃣ 8⃣ 6⃣ -021-02923-7, 2⃣ 0⃣ 2⃣ 1⃣