The wind was probably cheap on March 10 of the year 241 BC. But otherwise it didn't look good for the fleet of the old naval power Carthage. Actually, commandant Hanno had focused on the surprise effect and secretly wanted to land on the west coast of Sicily besieged by Rome. But the opponents were on the hat. And an advantage. The Roman teams were better trained, their ships only had the bare essentials on board and were therefore significantly more agile than the vehicles from North Africa overloaded with equipment and stocks. And so the doom took its course. The naval battle in front of the Aegadic Islands west of Sicily ended for Carthage in the disaster, more than half of the fleet was destroyed or captured. The first Punic War was decided in favor of Rome. And the scene of the event had turned into a sea cemetery littered with ships.

Today, this area is an exciting field of research not only from an archaeological point of view, but also from an ecological point of view. Because new life is teeming on the old rubble. For example, divers have recovered from a depth of around 90 meters of water one of those ramming spurs that were often attached to the bow of ancient warships: a hollow, 90 centimeters long and 170 kilograms heavy piece of bronze, with the help of which the enemy ship was to be rammed and sunk. As the researchers' investigations show: At the bottom of the Tyrrhenian Sea, the once deadly weapon has turned into a refuge for all kinds of aquatic inhabitants.

A team led by Maria Flavia Gravina from the University of Tor Vergata in Rome has discovered a total of 114 animal species on the surface and inside the spur. They had joined forces to create their own small town. "The main builders in this community are bristle worms, moss animals and some shellfish species," explains Edoardo Casoli of La Sapienza University in Rome, who collaborated on the study. "Their tubes, shells and colonies attach directly to the surface of the wreck." There are small bridges between them, which consist of the colonies of moss animals.

But where do all these residents come from? Apparently, add -ups from a wide variety of other habitats have gathered in »Rammsporn City«. Some come from seaweed meadows, others are usually in scorched flat water areas, on light -flooded rocks or in the rather dim reefs of the calcal genes. "On younger shipwrecks, the community is usually not as diverse as in the habitats in the surrounding area," says Maria Flavia Gravina. "There are mainly species whose larval stage takes a long time and which can spread widely."

Since the First Punic War, enough time has apparently passed to attract other inhabitants. In more than 2200 years, a cross-section of the marine life of the entire region has settled on the spur. There are long- and short-lived larvae, mobile and sedentary adults. Loners live next to colony inhabitants, sexually active species next to followers of virgin procreation. "Such old wrecks practically act as an ecological memory of their colonization," says Maria Flavia Gravina.

The crew of the Iron Eaters

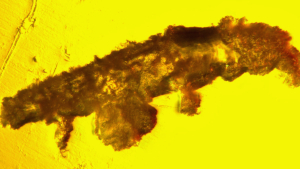

But the remains of significantly younger ships are also ecologically interesting. As soon as they lie without a human crew on the sea floor, they are teased by a new crew. Some of their members are so small and inconspicuous that not much is yet known about their activities. Like a film, countless bacteria, mushrooms and other microorganisms cover the gumps, planks and masts. And it is worth examining this hidden world more precisely. Because the microbes decide on the fate of the wreck and its other residents.

For example, a team led by Kyra Price from East Carolina University in Greenwich has taken a close look at the microorganisms that have settled on the Pappy Lane wreck. This former warship has only been lying in the shallow water of the Pamlico Sound in North Carolina since the 1960s. But the few decades have been enough to allow a diverse community of microbes to thrive on the steel hull. On the wreckage, the genetic material of 28 bacterial groups with very different lifestyles could be detected.

For example, organisms that gain their energy by oxidizing iron were prominently represented - in other words that produce rust. Such "iron eaters" have fairly fast enter teams in their ranks, which are probably one of the first settlers of steel surfaces. The team has found representatives of this group almost everywhere on the 50 meter long ship - but in different density and composition. Because steel is apparently not the same as steel from a microbing view. Perhaps there is a better range of iron or oxygen at one point than on another. Or in a former fuel tank there are still hydrocarbons that can use some microbes and others. In any case, such a sunken ship seems to consist of different ecological niches that have divided its residents among themselves.

New trunk on old ship

You can already see that from the outside of the wreck. For example, there were more and partly different bacteria on heavily rusted parts than on those that were still largely intact. The team even discovered a previously unknown strain of "iron eaters" from the group of Zetaproteobacteria at a corroded site and named it Mariprofundus ferrooxidans O1.

According to the team, such wreck residents should be kept in mind. After all, the activities of the iron oxidizers can certainly help transform valuable historical ships into rusty scrap. However, certain bacteria can possibly be used as an early warning system: If one could determine their occurrence in good time, the destruction might be slow. However, the results of the study also show that there is probably no a patent recipe for the preservation of shipwrecks: Each individual probably needs an individually tailored protective concept that takes into account the building materials as well as the various environmental factors and the time that has passed since the downfall. Because all of this affects which bacteria collect where.

Thus, in the tiny boarding teams, not only destructive forces are at work. After all, microbes not only decompose iron, but also boost a whole host of other chemical processes. For example, they play an important role in the cycles of nitrogen, carbon and sulfur. And in doing so, they keep their own small ecosystems running on the wrecks, whose influence radiates surprisingly far into the environment.

Microbial variety on the bottom

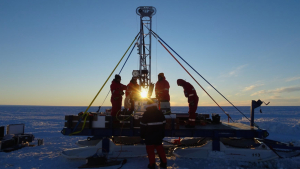

Leila Hamdan from the University of Southern Mississippi and her colleagues in the Gulf of Mexico are on the trail of such processes. There, for example, they examined the wreck of the luxury yacht Anona, which sank in 1944. Since this ship is more than 1200 meters below sea level in the deep sea, it has turned into an island of microbial diversity. And it does not end at the walls of the ship. Even 200 meters away from them, typical wreck inhabitants were still found in the sediment of the seabed.

The team came to similar results during an experiment on two wooden sailing ships from the 19th century, which are also located in the depths of the Gulf of Mexico. The researchers placed pieces of pine and oak wood in their vicinity at various distances and collected them again after four months. Using DNA analysis, they then examined all the bacteria, fungi and other microorganisms that had settled on it in the meantime.

In this case too, the wreck residents conquered the new habitats in their surroundings. They reached their biggest biodiversity from the ships up to 125 meters away, but even on the 200 meters away, their influence was still clearly recognizable. This is a surprisingly large radius. Also natural structures in the deep sea increase the biological diversity in its neighborhood. In the case of a walkadaver, which was sunken to the bottom, such an influence could only be demonstrated up to ten meters away, around the particularly species -rich methane sources it was about 100 meters.

Three million wrecks slumber on the seabed

Apparently, many microbes benefit from the wrecks in a very similar way to dead wood or rocks: there they find fixed surfaces that you can attach to. And they have rarity in the rather monotonous world of sand and mud that shapes the seabed in many places. "We have known for a long time that natural hard substrates have a major impact on biological diversity down there," says Leila Hamdan. "However, our study has now shown for the first time that people created by humans also decide which microorganisms settle on the hard surfaces in their area."

As a result, sunken ships could have a much greater ecological impact than had long been assumed. After all, according to estimates by the World Cultural Organization Unesco, about three million wrecks are slumbering at the bottom of the oceans worldwide. Each of these is a potential habitat for a rich microbial community. And this, in turn, can create food and livelihoods for numerous other organisms. "It is ultimately due to these biofilms that the hard surfaces on the seabed are transformed into oases of diversity," says Laila Hamdan.

How successful you are can also be visited on the Dutch continental car. In this area of the North Sea, the soil nowadays mostly consists of sand and other soft substrates. You can hardly find hard surfaces. But that was not always so. Old maps and research reports show that in the 19th century between 20 and 35 percent of the marine base there were covered with oyster banks, boulders from the ice age and other hard substrates. Due to erosion, destructive fishing practices and the extinction of the oysters, these habitats have now almost completely disappeared. However, this does not apply to their residents: a number of species that rely on a solid surface have apparently found a new home on sunken ships.

Wreck replaces destroyed oyster beds

This was the conclusion of a study conducted by the private research company Bureau Waardenburg on behalf of the Dutch government. The team led by marine ecologist Joop Coolen has examined ten wrecks that are located up to 75 kilometers off the coast. The researchers came across a total of 165 animal species. Five of them had never been detected in the Netherlands at all, of 64 others no one had known that they were found on the continental shelf. Each wreck had its own unique community with several species that did not appear anywhere else.

Although the lost ships only take a tiny part of the sea area, an unusually high biodiversity concentrates here. And for a number of residents they have probably become the last rescue. The Atlantic cod (Gadus Morhua), the cliff bass (Ctenolabrus Rupestris) and the Leopardrundel (Thorogobius Eppippiatus) can be found there and protection against fishing.

The researchers think it is quite possible that some of these fish would have disappeared from the region altogether if there were no shipwrecks. The same applies to species such as the whelk (Buccinum undatum) and the primed dwarf squid (Alloteuthis subulata), which attach their eggs to solid surfaces. Or for cave dwellers such as the pocket crab (Cancer pagurus) and the European lobster (Homarus gammarus).

Hope for the European oyster

Perhaps the sunken seafarers' heritage may even offer new opportunities for the European oyster (Ostrea edulis). There used to be huge stocks of this popular seafood in the North Sea. But too intensive fishing decimated them massively in the 19th century. In Germany, the species became »functionally extinct« by the 1950s at the latest. So there are too few animals to rebuild healthy populations on their own. The mussels are doing similarly badly in the Netherlands. Recently, some populations have been discovered near the coasts there. On the high seas it is considered extinct.

But there must still be a stock somewhere there that can multiply. An indication of this was found by Joop Coolen, who now works at the Dutch Marine Research institute Wageningen Marine Research, in July 2019. In a depression next to the wreck of a steamship that sank about 100 years ago northwest of the island of Texel, he and his team came across a European oyster. Three to four years old and still alive. The researchers found another specimen during a dive in September of the same year directly on the speedboat escort ship Gustav Nachtigal, which the British Air Force sank off the island of Schiermonnikoog in 1944.

So far, nobody knows where the larvae of these mussels came from. But they have reached their new home on their own - and found cheap conditions there. According to the researchers, this makes the wrecks of promising bodies for the resettlement of this kind. Apparently on old ships is also attractive for endangered sea creatures.