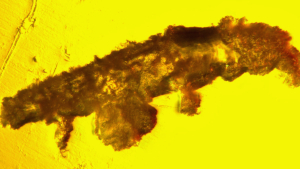

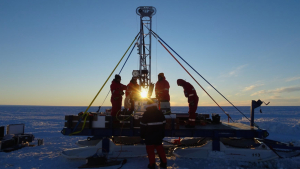

Compared to his relatives that still live today, Enhydiodon Omoensis was a giant. The now extinct Otter was as large as a lion and weighed around 200 kilograms - around five times as much as the Pacific seater (Enhydra Lutris). At the shoulder height, he exceeded the South American giant otter (Pteronura Brazil) by twice. Kevin Uno from Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and his team have dug up the giant's fossils in Ethiopia and describe the find in the journal "Comptes Rendus Palevol".

The species lived about 3.5 to 2.5 million years ago; its name is derived from the site in the lower Omo Valley in southwestern Ethiopia. "In addition to its size, the special thing about the otter is that, unlike today's otters, it probably lived mostly on land. This is indicated by certain isotopes in his teeth, " says Uno: "He mainly ate animals living on land and not aquatic creatures like his modern relatives." The working group derived height and weight from the found teeth and thigh bones.

Very large types of otter are known from Europe, Asia and Africa from six to two million years ago, but no previously known species reached the dimensions of Enhydriodon Omoensis.

The species Siamogal Melilutra from East Asia, for example, became wolf -sized, but mostly lived aquatic.

Initially, Enhydriodon omoensis was considered to be at least semiaquatic, since other known species of the genus feed on mollusks, turtles, crocodiles and catfish, which are common in African freshwater areas. Uno investigated whether this also applied to E. omoensis by analyzing stable oxygen and carbon isotopes in the tooth enamel.

The relative values of the stable oxygen isotopes can give an indication of the habitat that an animal inhabits. Actually, the values of the fossil otter should have been close to the values of fossil hippos or other animals who live in the water and look for food there. Instead, the OMO-OTERS showed values that corresponded to those of land mammals, especially large cats and hyenas from the region's fossil deposits. The marten therefore mainly eaten tropical herbivores. Why the species ultimately died out, UN and Co want to clarify with the help of further excavations.