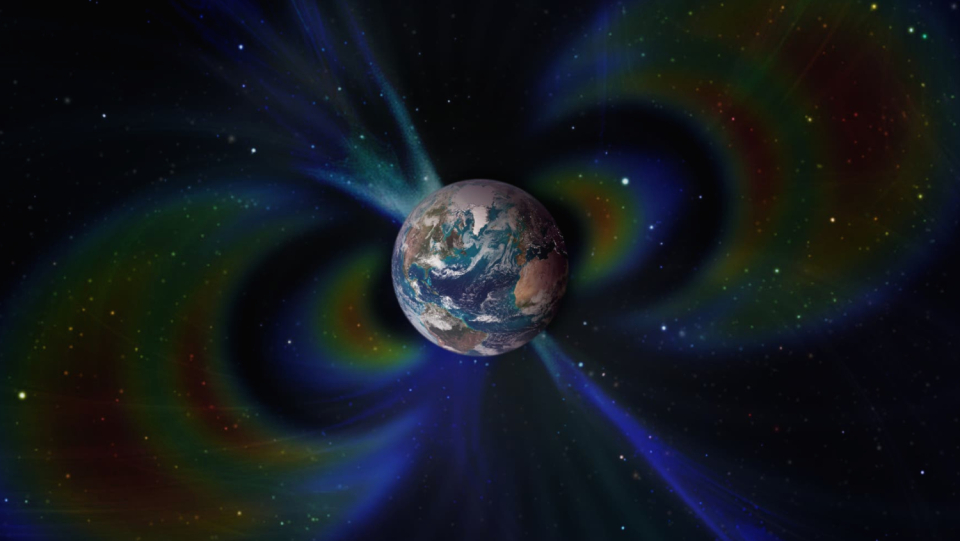

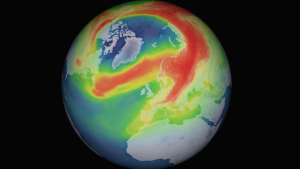

The "hole" in the Earth's magnetic field over the South Atlantic is probably not a sign of an imminent magnetic field reversal. This is the conclusion reached by a working group led by Andreas Nilsson from Lund University using a new model of the magnetic field over the last 9000 years. As the team reports in PNAS, zones with an unusually weak magnetic field such as the South Atlantic Anomaly occur from time to time, most recently around 2600 years ago.

The model is based on measurements on archaeological finds, deep-sea sediments and volcanic deposits, which provide information about the orientation and strength of the magnetic field at specific locations and times. The results show that strong regional anomalies are related to regular fluctuations in the dipole moment of the magnetic field. Accordingly, the Earth's magnetic field should soon become stronger and more symmetrical again and the South Atlantic "hole" should disappear again in the next few hundred years.

The analysis is the question of how unusual the behavior of the magnetic field is currently - and whether it announces a dramatic change. The earth's magnetic field has become significantly weaker in the past around 200 years, and since the late 1990s the North Pole has been moving by about 50 kilometers a year - more than three times as quickly as before. This and the pronounced zone with a very weak magnetic field above the South Atlantic interpreted some experts as signs that the earth's magnetic field could soon change its polarity.

Such pole jumps were frequent in the history of the earth. For humanity, such a "pole shift" would presumably have serious consequences. The magnetic field would probably almost disappear for centuries, possibly with considerable effects on the Earth's climate. This would also be a problem for technology, satellites, for example, would be fully exposed to the solar wind.

However, the theory of the pole shift is very controversial, because the behavior of the field is only very incompletely known. It is extremely difficult to deduce the behavior of the magnetic field over short periods of time from physical measurements on samples. The team led by Nilsson therefore tried to smooth out the uncertainties in the measurement data with a statistical method and to obtain a consistent global model. The analysis revealed evidence that the field fluctuates on timescales of millennia between quite symmetrical states with a strong dipole character and states with less dipole character and large asymmetries, such as the South Atlantic Anomaly.

Accordingly, the current state of the earth's magnetic field is simply a relatively typical, recurring pattern. There have been comparable phenomena in the past 9000 years because the field strength fluctuates significantly globally and locally. According to the team, a pole jump is therefore not imminent, on the contrary.

In the next few hundred years, the field will probably become more symmetrical again, and the South Atlantic anomaly will disappear again. The conclusions of the study are consistent with the results of various research in the field. Other investigations had also shown that the Earth's magnetic field is very variable and its current behavior is probably not an indication of upcoming dramatic changes.