In less than a decade, it could be so far that a spaceship flies past the earth from Mars to deliver a precious freight: rock samples and even air samples of the red planet. With the help of these rehearsals, a small army of researchers would love to find signs of extraterrestrial life: life from Mars, right here on earth. The ambitious endeavor costs several billion euros and is promoted by the U.S. Welfare Authority NASA and the European Space Agency ESA. It is the "Mars Sample Return" program (MSR). And it is something like the holy grail for planetary researchers.

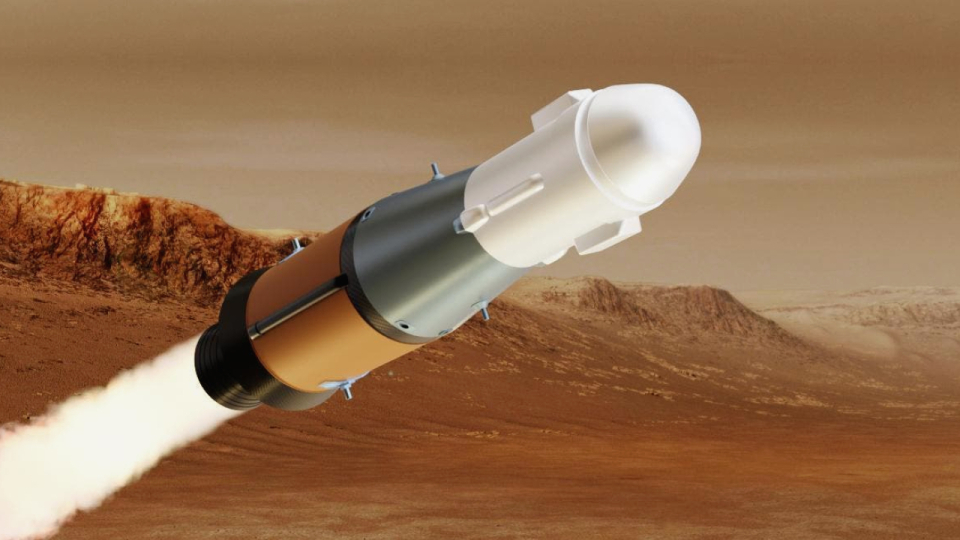

In many ways, MSR is already in full swing: because the Marsrover Perseverance of NASA drives around in a former river delta of the crater Jezero on Mars. The rover collects rehearsals of potential astrobiological interest and leaves them on the surface of the red planet. The rehearsals could later be collected by another rover. A so -called "Mars Ascent Vehicle" (MAV) is currently being designed and tested: This MAV would bring the rehearsals into the orbit of Mars. According to the current plan, a spaceship would be waiting there that brings the rehearsals back to earth.

But there is this one aspect of the program, a problem that has not yet been solved: how exactly should NASA and ESA deal with the rock samples here on Earth, and how much can this cost? The question is not entirely trivial. After all, no one wants to accidentally contaminate the Earth's biosphere with imported life from Mars.

Could contamination of the earth result from the Mars Sample Return program by mistake?

The solution to this problem could fundamentally shape not only the MSR program, but also the potential human visit to the Martian surface: could astronauts live and work on Mars without accidentally contaminating the Red Planet with terrestrial microbes? And could these visitors to Mars then return home with a clear conscience, please without microscopic Martian hitchhikers on board? The protocols that will be developed for the MSR program will play a crucial role in solving these future problems.

The current NASA proposal for MSR provides for an unexplored interplanetary ferry to release a conical capsule, filled with marshy, the so -called »Earth Entry System« high above the atmosphere of our planet. The capsule will then fall onto the earth without parachuts and land in Utah. Despite the impact at a speed of around 150 kilometers per hour, the capsule will be built in such a way that the samples contained therein are protected and isolated from the outside world. As soon as the capsule has been recovered, it is sent to an external sample annex in a protective container. Such a facility could be similar to organic laboratories that examine high -containing pathogens and include multi -stage decontamination measures, air filter systems, vacuum fans and countless other safety precautions.

The NASA classifies the risk through rock samples from Mars as extremely low

NASA relies on the results of several expert bodies if it currently classifies the ecological and security -relevant risks of the proposal as "extremely low".

But not everyone agrees to this plan.

At the beginning of the year, NASA asked for the public comments: it was about a draft of the environmental declaration of environmental impact on its project.

There were 170 comments.

Most of them were negative about the concept of the Marsproben to Go.

“Are you crazy? Not just no, but damn no, «is a comment. "No nation should endanger the whole planet," said another comment. And a third comment states that the headwind will increase as soon as NASA's intentions would continue to be known. Many of the respondents suggested that the rehearsals should first be received and examined beyond the earth. This is a prudent idea, but it could become a logistical and costly nightmare.

Contrary to all this caution, the prominent astrobiologist Steven Benner takes an outspoken opinion. He says: "I don't see the need for long discussions about how to deal with the Martian samples as soon as they reach our planet." This is partly due to the fact that the Earth is repeatedly hit by meteorites that originally came from Mars. According to Steven Benner, current estimates assume that around 500 kilograms of Martian rocks land on Earth every year. As if to prove it, a five-gram piece of Martian rock is lying on his desk.

"In the more than 3.5 billion years since life has been created, trillions of other rocks have made similar trips," says Benner. »If Mars microbes exist and the biosphere of the earth can devastate, this has already happened. Then a few kilograms no longer make a difference. "

Benner is a member of many of the expert committees that NASA has consulted to arrive at its "extremely low" risk assessment of the project. The astrobiologist believes that NASA is now trapped in its own PR trap: it has virtually committed itself to endlessly discussing the alleged complexity of what should actually be simple, well-founded science. NASA now knows "how to search for life on Mars, where to search for life on Mars and why the probability of finding life on Mars is high," says Steven Benner. "But the committees within NASA want consensus and agreement on fundamentals of chemistry, biology and planetary sciences. But these would have to be considered as the basis for the search for life on Mars. Thus, science is displaced in favor of discussions about problems that actually do not exist." This would unnecessarily increase costs. This would delay the launch of missions.

"And in the end you make so sure that NASA will never carry out any missions about the discovery of life," says Steven Benner.

Planetenschutz vs. Mars Probe Retraction

Such statements reflect the urgency with which American planetary scientists want to implement the Mars Sample Return program. NASA received an important report in April: The so -called Decadal Survey deals with planetary science and astrobiology and is created by the USA. He defines the priorities in these research areas for the coming years. A recommendation of the report is that NASA should concretize its plans for dealing with the Mar sample. The focus must be on providing a suitable facility so that it could receive material from the red planet by 2031.

To meet such a deadline, NASA must immediately begin the design and construction of such an institution, says Philip Christensen, a professor at Arizona State University and co-chairman of the steering committee of the new Decadal Survey.

"Our recommendation was not to build a very unusual and very complicated reception device full of instruments," says Christensen. »But: make it as easy as possible. Because the most important task is to check whether the samples are safe. Then you can pass them on to laboratories around the world that already have highly developed instruments. «

John Rummel is a retired astrobiologist. Previously, he led NASA's efforts on the topic of "Planetary Protection", i.e. on the safety measures for our planet during interplanetary missions. Rummel agrees with the statement that a simple setup could save time. However, he is not so sure about the cost. "No one wants to spend all the money in the world on a kind of Taj Mahal for rock samples," he says. But the construction of a very simple system could also backfire: perhaps scientists would then not be able to properly investigate whether the so precious samples contain evidence of life.

Rummel says that it is basically not true that we know enough about Mars to quantify the risk of interplanetary contagion by the samples of the MSR program. “We don't know everything we want to know about Mars. That's why we want the rehearsals, «says Rummel. “And we always find that earth organisms do new things that are quite interesting in terms of potential aliens. So we have to be careful, as the research council emphasizes again and again. "

With the Mars sample return program, environmental protection for Earth need not be expensive.

The real risks of the MSR program as far as interplanetary environmental disasters are not known.

But most participating scientists are clear what threat is a negative public opinion for the mission.

Nevertheless, contact with the public should be welcomed, says Penny Boston, astrobiologist at the AMES Research Center of NASA.

She argues that there was hardly a better way to close the research gaps to protect the planet than to arouse people's interest in this topic.

»Then we can optimally protect both the biosphere of the earth and the people on it.

And at the same time we can use the analyzes of the Mar sorts to answer the scientific questions, «says Penny Boston.

Now it seems more likely that strict handling restrictions for MSR samples will have a deterrent effect than that an extraterrestrial pandemic will break out due to lax safety protocols. But would it really be that much more expensive to play it safe?

The astrobiologist Cassie Conley was John Rummel's successor from 2006 to 2017 as a Planetary Protection Officer of NASA. She says: »Taxpayers will have invested at least ten billion US dollars to bring the rehearsals to earth. In view of this amount, it is therefore not worth output one percent more in order to build the best possible facilities and instruments for the examination of those samples and at the same time ensure that MSR does not cause damage to the only planet on which we can live? "

The souvenirs from Mars are already controversial

And something else complicates the debate: because the Mars sample return program is no longer alone in its hunt for fresh rock samples from Mars. And other projects may not adhere to the rules that have not been established so far. China recently announced independent plans to bring material from Mars to Earth. Perhaps China would be able to do this even earlier than NASA and ESA. And then there is also Elon Musk and the efforts of his company SpaceX to bring people to Mars and back again – and perhaps much earlier than most experts expect.

China's plans worry the astrobiologist Barry Digregorio, founding director of the International Committee against Mars Sample Return. "As long as it is not a worldwide undertaking and the results are shared with all space nations in real time, no single country will know what the other country has found or what problems it has with containment," he says.

That's why Barry DiGregorio would be in favor of first making sure for each individual sample that it does not pose a danger to our planet before it is allowed to get to Earth. And this could best be done in a specially equipped space station or in an astrobiological research laboratory as part of a lunar base. DiGregorio also acknowledges that this concept is difficult to sell in the face of global political tensions. But now is the critical time to at least consider it.