If humanity has ever discovered life beyond the earth, then the first question is probably that arises: "How can we communicate with each other?" And since the 50th anniversary of the Arecibo message names-that was the first attempt by mankind in 1974 , to send a message that is understandable for extraterrestrial intelligence - this question seems to be more urgent than ever. Progresses in remote sensing technology have also shown that most stars in our galaxy accommodate planets and that many such exoplanet could have liquid water on their surface, which is a prerequisite for life. So it is at least likely that at least one of these billions of planets has produced intelligent life. It is therefore worth finding out how best to say "hello".

At the beginning of March 2022, an international research team led by Jonathan Jiang from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory published a preprint study, which has since been published in the journal "Galaxies": the working group presents a new idea of what a message to extraterrestrial recipients might look like. Her 13-page letter, which is called "A Beacon in the Galaxy", contains basics of mathematics, chemistry and biology. The design is strongly based on the Arecibo message, as well as on previous attempts to contact extraterrestrials. The researchers have also presented a detailed plan for when the best time to send the message is and where the message should go: in the direction of a dense ring of stars near the center of our galaxy. In addition, the message contains a newly formulated sender address. With this, the alien receivers should be able to determine our location in the galaxy and – hopefully – start an interstellar conversation with us.

"The motivation for the [new] design was to pack a maximum of information about our society and the human species in a minimal message," says Jiang. "Due to the advanced digital technology, we can do this much better than in 1974."

Looking for common ground

Every interstellar contact signal has to deal with two questions in particular: what should be said and how should it be said? Almost all the messages that humans have sent into space so far are aimed at possible mutual knowledge by containing basic knowledge from the natural sciences and mathematics – two areas that could be familiar to both us and aliens. And if a civilization beyond Earth is able to build a radio telescope to receive signals with it, then it probably also has knowledge of physics.

However, the question of how these concepts are to be encoded in the communication is far more complicated. Human languages are obviously out of the question, but the same applies to our number systems. Although the numbers themselves are almost universal, the human display methods as digits are basically arbitrary. Therefore, many experts have so far decided, including "Beacon in the Galaxy", to design their letter as a bitmap. Such a binary picture offers the opportunity to create a pixelated picture with the help of a binary code.

The idea of using a bitmap as an interstellar means of communication goes back to the Arecibo message. It seems logical to assume that a binary image that conveys content based on/off or there/non-there is probably understood by any intelligent species. But the strategy is also flawed. SETI pioneer Frank Drake (SETI, Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) once mailed a draft of the Arecibo message to colleagues, including several Nobel laureates. None of them were able to understand the content, and only one found out that the binary message was supposed to be a bitmap. If rather smart people have difficulty understanding this form of coding, it is unlikely that aliens would succeed better. Moreover, it is not even clear whether they could visualize the images contained in the message.

"Because vision has evolved more frequently and independently on Earth, one of the main assumptions is that aliens also have it," says Douglas Vakoch, president of Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence (METI) International, a non-profit organization that conducts research on ways of communicating with other life forms. "But this is a very big "case", and even if you can see, our way of depicting objects is strongly culturally conditioned. Does it follow from this that we should completely exclude pictorial representations? Not at all. But it means that we should not naively assume that our representations will be understandable.«

When Cosmic Call 2003 sounded

In 2017, for the first time since 2003, Vakoch and his colleagues sent an interstellar message to a nearby star to transmit scientific material. This message was also binary coded, but the researchers dispensed with binary images. Rather, they drafted a message that referred to the radio wave itself, which carried the content. Jiang and his team chose a different path. They based their design largely on Cosmic Call, a message broadcast by the Yevpatoriaradio telescope in Ukraine in 2003. This message contained a special bitmap alphabet designed by physicists Yvan Dutil and Stéphane Dumas as a precursor to an alien language. In this way, transmission errors should be avoided.

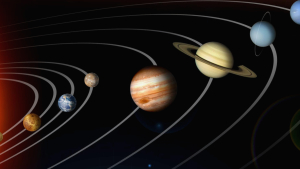

After the first transmission of a prime number to mark the message as a deliberate signal, Jiang & Co want to use the same alien alphabet. They thus introduce the decimal system and basic mathematics. In addition, the message contains the spin-flip transition of a hydrogen atom to present the idea of time and explain when the message was sent from Earth. In addition, we are talking about certain elements from the periodic table, as well as the structure and chemistry of DNA. The last pages of the message might be the most interesting for aliens, but they are probably not very understandable: they assume that the recipient represents objects in the same way as people. These pages contain the sketch of a man and a woman, a map of the Earth's surface, a diagram of our solar system, the radio frequency that the aliens should use for their answer, as well as the coordinates of our solar system – marked by globular clusters, that is, dense groups of stars that aliens would probably recognize.

"We know the location of more than 50 bullet star heaps," says Jiang. "We therefore assume that an advanced civilization, which is familiar with astrophysics, also knows the locations of the globular clusters, so that we can use them as coordinates to determine the location of our solar system."

Jiang and his colleagues propose to send their message either from the Allen Telescope Array in Northern California or from the FAST radio telescope in China. Since the collapse of the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico, only these two radio telescopes have granted access to SETI researchers. However, at the moment, both telescopes are only able to eavesdrop into space, not communicate with it. Jiang admits that it will not be easy to equip one of the two telescopes with the necessary equipment, but it is possible. Jiang is in contact with the experts of the FAST telescope for this purpose.

March or October would be ideal months.

If Jiang and his team are actually allowed to get started, then the best time for this would be sometime in March or October of a year, when the Earth is at a 90-degree angle between the Sun and its destination in the center of the Milky Way. Then the message would most likely not go down in the background noise of our sun. However, one question is still unresolved: whether we should send a message at all.

The transmission of messages to extraterrestrials in the SETI community has always been considered a controversial undertaking. Because it should actually be the goal of capturing extraterrestrial transmissions not to send in. The representatives of that SETI philosophy consider it a waste of time and in the worst case to send signals. So there are billions of possible target points, and the likelihood that at the right time a message will go out to the right planet is negligible. It is also not clear who could listen to everything. What if we pass on our address to an extraterrestrial species that feeds on two -legged hominins?

"I'm not afraid of an invading horde, but other people have them. And just because I don't share their fear, their worries aren't irrelevant," says Sheri Wells-Jensen, a professor of English at Bowling Green State University and an expert on language and culture in shaping interstellar messages. Just because it's difficult to reach a global consensus on what to send or whether to do it doesn't mean we should stop it altogether. It is our responsibility to deal with this and to involve as many people as possible.«

Many experts also consider it more advantageous to actively seek contact. A first contact would represent the most significant event in the history of our species – on the other hand, if humanity were just waiting for a call, it might never come. Some SETI researchers are also pragmatic about the risk of calling malicious aliens on the scene: humanity has actually betrayed itself a long time ago. Any alien that can travel to Earth would probably also be able to detect the chemical signatures of human life in our atmosphere or to capture electromagnetic radiation that has been coming from radios, televisions and radar systems for a century. "All people on Earth are invited to participate in the discussion about the message," says Jiang. "We hope that by publishing this study, we will make people think.«