It was probably the last cheetahs in India that Maharaja Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo met and killed one night in 1947. With this, the ruler of the principality of Koriya probably sealed the fate of animals in India. With two well-aimed shots, he killed three males on the edge of a road. A black and white photo shows him posing behind the predatory cats after the hunt. To date, it is the last evidence of the sighting of a cheetah in India. The habitat of the animals had steadily shrunk in the decades before, there was a shortage of prey, and cheetahs were considered pests under the British colonial power. After the Maharaja's hunt, there were only rumors of sightings, in 1952 India finally declared the species officially extinct. But now the cheetahs are returning to the subcontinent, having flown in from the south of Africa. In the official action plan, Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav speaks of a "globally important species protection project".

Eight cheetahs from Namibia were exported to their new home in mid -September. However, the cheetah is also threatened in Africa: it is the rarest big cat in the continent. There are only around 6,500 adult copies all over Africa. The Asian subspecies are even worse: the only remaining population lives in Iran. In 2018, researchers estimated that it consists of fewer than 40 animals. As early as the 1970s, India had tried to negotiate a deal with the neighboring country. The advances failed; Tehran did not want to do without any of his endangered animals. So you turned to the last strongholds of the cheetah in the south of Africa. With success.

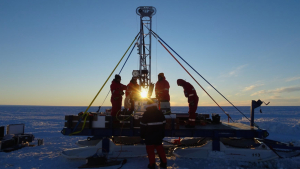

Her trip was like a national spectacle: the Indian government chartered a Boeing 747 in tiger design, in the stomach of the jumbos the cheetah covered around 8000 kilometers. In the Kuno National Park, India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi personally welcomed the founding population. "The long wait is over, the cheetahs have a home in India," modes tweeted later.

Laurie Marker and her team from the Namibian Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) did not take sight of the five females and three males throughout the trip. For months they had prepared the animals for long transportation, checked their health, organized the necessary permits. "It is one of the biggest resettlement projects that have ever existed in species protection," says Marker. The CCF chairman has been advising the Indian government since the mid-1990s. With relocations within Africa, markers and their team have experience. That is also why she shows itself optimistically: "The plan is ambitious," says Marker, "but the government has commissioned the right people with it."

It is not the first PARD resettlement campaign: In Malawi, scientists have succeeded in resettling the cheetah after 20 years of absence. In 2017 they brought four males and three females to the Southeast African country. In the meantime, the population in the Liwonde National Park consists of more than 20 animals. For five years, researchers monitored any movement of the animals. Your intermediate conclusion: the cheetah population not only remains, it continues to grow.

The animals from Namibia are to find a new home in the Central Indian Kuno National Park. In the middle of the Monsun season, the last preparations are also running there: Ranger stalls the area with prey, the mascot "Chintu Cheetah" is intended to tune in the local population to the return of the big cat. A total of 50 cheers from several South African countries are to be brought to India over the next five years.

In the first few weeks, the animals come under fenced enclosures. After the familiarization period, they should be released into the wilderness of the national park. The researchers calculated in advance that the 750 square kilometers of space offers enough habitat and prey for a maximum of 21 cheetahs. Later the habitat is to be enlarged to up to 3200 square kilometers. According to the plan, this would be enough space for 36. Until then, it is still a long way. "It will take many years for us to have a viable population in India," says Marker. "We'll probably also lose animals."

An experiment at the expense of cheetahs and humans?

Science is disagreed with whether the possible benefits justify the risk. Bettina Wachter from the Berlin Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) says that it is an "interesting experiment", but also warns: "Maybe the expense of the cheetahs that do not exactly occur."

Wachter and her team have been researching the big cats in southwest Africa for about 20 years. "750 square kilometers is nothing for cheetahs from Namibia," she says. In the sparsely populated country, dominant males occupy a territory of an average of 390 square kilometers. Males without their own territory roam an average of 1500 square kilometers. Cheetahs exchange messages via a kind of social network: every 23 kilometers there is a selected "hotspot" – usually it is a tree – on which they leave scent marks. "It seems unlikely to me that a population in the wild can maintain its communication system on such a small area," says Wachter. "This does not work out in purely mathematical terms.«

Turned are considered adaptable. In the Serengeti in Tanzania you will find your way around as well as in the desert country Namibia. And at least the Asian subspecies was once native to India. But it is a difference whether an animal adapts to new environments over generations or whether you put it on a plane and put up again for thousands of kilometers away, says Wachter: »This could be a shock for the immune system, as it could be on from now on immediately meets many new pathogens. "

Actually, Kuno National Park was intended for another predator, the Asian lion. At the end of the 1990s, the former reserve became a national park, more than 5000 people had to evacuate their villages. As compensation, they received a piece of land outside the protected space. But the lions never came – which is why it was decided to settle the cheetahs in Kuno. Before arrival, the last remaining village should also clear the national park.

"In the name of species protection, the poorest of the poor is asked to leave their home," says Asmita Kabra from the Ambedar University in Delhi. The economist has researched how the relocation affects the affected people. “When they had to leave the reserve, they lost their livelihood, and their new country was not enough to cultivate. Indigenous communities were sent out of their forest and made them cheap workers. ”Her animals have largely left the former farmers behind because there was no water and no food for them at the move. They should now serve as prey for the cheetah.

The conflict between humans and animals is ancient. In Namibia, Wachter observed him again and again. Because cheetahs tore their calves, farmers shot the big cats. The researchers from the Leibniz-IZW have worked together with the livestock farmers, collected data together with them, and developed strategies for peaceful coexistence. All this is only possible in close coordination and with scientific support, says Wachter. The fact that the Indian government has entire villages evacuated in advance has led to criticism. "Our belief systems contain many elements associated with animals, plants, and nature in general," says wildlife biologist Ravi Chellam, who has studied Asian lions for decades. However, politicians ignore this special relationship.

The desire for more tourism against reason

In the long term, people should come to the park again: wealthy safari guests. Because the arrival of the cheetahs plays a new trump card to the tourism industry. If the settlement succeeds, India can advertise with four big cats in the wild: cheetahs, lions, tigers and leopards.

However, the other predators could endanger the newcomers from Africa. The cheetah is the fastest mammal in the world, but it is mercilessly inferior to its competitors because of his building. Wachter and her colleagues recently noticed this in Namibia. The cheetah population shrinks slightly in its study area-because more and more leopards are coming. "As soon as competitors are there, the pressure is increasing and decreasing," says Wachter.

The leopard density in Kuno is high, this is referring to the action plan. However, the authors consider coexistence to be possible as long as there is sufficient prey. The zoologist Marker is also confident: "The animals from Namibia and South Africa are used to other predators." After the relocation, teams from Namibia and India are supposed to pursue and observe the cheetahs with the help of radio neck bands. Watch towers were built, cameras were installed. But completely protecting, says Marker, you can never do animals in the wilderness.

In India, the cheetahs should in future serve as an ambassador for species protection. "The cheetah is a so -called top robber," says Marker, a predator that has no predators, "if we can bring it back, then this will promote the entire variety of biodies in the savannas." At least in Malawi, this calculation has been reported Researchers. There, the return of the cake ensured that other species followed him naturally, for example the heavily endangered vultures.

"We need to change the narrative so that savannas in India finally become the focus of species protection," says ecologist Stotra Chakrabarti from the Macalaster College in the USA. A charismatic predator such as the cheetah, the researcher believes, can draw interest to endangered roommates such as the Hindu bustard. Critics like Chellam are hardly convinced by the argument. "In 15 years, 21 cheetahs are expected. How will you save the savannas and forests all over India?"he asks. "And: shouldn't we save the habitat first before bringing the mammal here?«

If it is based on the driving forces of the project, India will only be the beginning. "There are a number of countries that want to get the cheete back," says Marker. What would need to need are new habitats, enough prey - and the help of man. "We will do everything for the project to succeed," says Marker. After all, there are not many cheetahs on earth. The fastest big cat in the world runs away.