Because she is not allowed to enter her laboratory in spring 2020 due to the corona pandemic, behavioral ecologist Daniela Rößler begins to catch native jumping spiders. She keeps them in transparent plastic boxes on her windowsill to test her reactions to predatory spider models from the 3-D printer. But when she comes home from dinner one evening, she notices something strange. "They were all hanging on the lid of their boxes," says Rößler, who is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Konstanz. Never before had she seen jumping spiders dangling so motionless from her silk thread. "I didn't know what had happened," says Rößler. "I thought they were dead."

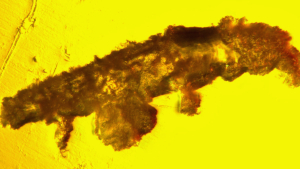

It turned out that the jumping spiders were simply sleeping – and that Rößler had discovered an alternative sleeping habit of the species Evarcha arcuata, which was previously only known to build silk sleeping cavities in rolled-up leaves. But the real surprise came when she decided to watch the animals all night long. The scientist bought a cheap night vision camera, glued some magnifying lenses on it (E. arcuata is usually about six millimeters long) and pointed them at a sleeping spider female. What Rößler saw on the recording amazed her.

Most of the time the spider just hung there. But then suddenly her legs began to twitch, her abdomen and even her silk -producing spider warts. Sometimes the legs rolled up towards the sternum. With every spider that Rößler recorded with the camera, these strange movements were expressed as short seizures, which usually lasted a little longer than a minute and occurred at regular intervals during the night. "They shrugged uncontrollably in a way that looked very much as when dogs or cats dream and have their short rem phases," she says.

Can spiders dream?

REM sleep (rapid eye movement) is a state of partial or almost complete muscle paralysis, coupled with an active, awake-like state of the brain, which is why it is sometimes also referred to as "paradoxical sleep". In humans, this condition is closely associated with dreaming. Rößler and her colleagues wondered if the twitching spiders could experience something like a REM phase of sleep and possibly even dream. "We thought, "Okay, that would be crazy,"" she says. The next moment she decided: "Let's find out, " and immediately changed her research plans for the spiders.

There are numerous evidence of REM sleep or a comparable condition for many mammals and birds.

In addition, scientists have already found something similar in two types of reptiles and even discovered it in zebra hints.

Both octopuses and ink fish seem to have a rem phase that is associated with eye movements, arm twitches and fast changes in skin color and structure, which resemble their behaviors in waking state.

Apart from these animals, there are only a few indications that invertebrates, including insects and arachnids, fall into a REM sleep phase.

"It wouldn't surprise me at all if jumping spiders have dreams," says behavioral ecologist Lisa Taylor, who studied the spiders at the University of Florida and was not involved in the new study. "They live in an extremely rich sensory world. We also know that they have amazing cognitive abilities and a good memory."

The jumping spiders provide a unique opportunity to expand the range of dreaming animals, also because of some peculiarities of their eye anatomy. While most spiders can't move their eyes even when awake, jumping spiders have long tubes that allow them to move their retinas back and forth behind their big main eyes. In addition, the exoskeleton of spiders is transparent in the first days of their life, so these eye tubes are even visible inside the head.

When Rößler looks at the records of 34 sleeping spider babies, she realizes that their twitching of movements of the eye tubes are accompanied that do not occur in other sleep phases. The videos also fascinate other researchers. "It is wonderful. I mean it's crazy. It immediately lets a sleep researcher think of the ›Rapid-Eye-Movement‹ sleep, «says entomologist Barrett Klein, who researches the sleep of bees at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. "To have the first indication that you can examine something like this and that it is relevant even with arthropods is really exciting."

However, it is still too early to say with certainty that spiders experience something similar to human REM sleep, Klein points out. According to him, the researchers involved in the study would first have to prove that the spiders actually slept during this phase by showing that the animals react worse to their environment.

Muscle paralysis is typical of REM sleep

Rößler and her co-authors have already started with these tests. They also point out that the curling of the legs is a particularly striking aspect of the REM-like phase of spiders, because this pose is usually only observed in dead spiders. Spiders build up a hydraulic pressure to keep their legs stretched, which is maintained by the muscles. The curling of the legs could be due to the muscle paralysis typical of REM sleep. They have now published their first results in "PNAS".

The videos alone are quite convincing, says Niels Rattenborg, who deals with the sleep of birds at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Intelligence in the Upper Bavarian Seewiesen and was also not involved in the study. "If I had to bet for money, and that is not very scientific, I would say that they sleep," he says. "The movements simply don't look as targeted as those who make spiders in the awake state."

Measuring tiny brains is a challenge

In order to show that the sleep of the arachnids is REM-like, the scientists would have to prove that the brain of the spiders is active as they twitch and move their eyes, says Rattenborg. Measuring activity in a poppy seeds of a poppy seeds will probably be a challenge, but according to Rößler there are opportunities for this. So other scientists recently found out how to introduce an electrode into the brain of another jumping spider type without destroying and killing the spider's body under pressure.

"The examination of REM sleep in a variety of species, including these spiders, could help us understand how it works and why it exists," says Rattenborg. Some researchers have drawn up the theory that the characteristic eye movements of REM sleep reflect visual scenes in humans that take place during dreaming. This results in the exciting idea that other animals that have a rem-like state also experience dreams. Of course, scientists cannot ask animals about their dreams, but the measurement of brain activity could one day be another way to get to the bottom of the question. The neuroethologist Teresa Iglesias, who deals with the sleep of head feet at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan, says: »We are still learning which patterns of brain activity are related to dreaming in humans. So it is still too early to expect to be possible to identify dreams physiological in other animals in a physiological way. «

As evidence mounts that nonhuman animals dream, the philosophical implications are potentially enormous, says David Peña-Guzmán, a philosopher at San Francisco State University and author of When Animals Dream: The Hidden World of Animal Consciousness. Dreams offer an introduction to questions of consciousness in other animals: it is hard to imagine that a simple dream is possible without something like an ego or a "me" experiencing it, he adds. So when spiders dream, "it could mean that we start talking about something like a minimal self," says Peña-Guzmán.

The visible eye tubes of the jumping spiders could help test the theory that fast eye movements are related to visual dream sequences, and to check whether these scenes are repetitions of things that have seen the arachnids in the awake state, says Daniela Rößler. For example, one could play a video of a simple scene, such as a bouncy grill, and follow their eye movements in order to see whether these movements are re -enacted in sleep.

Rößler also wants to look for REM sleep in other spider species and points out that it could look completely different in animals that rely more on senses other than sight, for example in spiders that use vibrations in their webs to recognize when they have caught prey. "Maybe the weavers' servants vibrate when they dream," she says. "I think that the REM phase is just as universal in the animal kingdom as sleep, but we just haven't looked for it enough yet.«

© Springer Nature Limited Scientific American, Spiders Seem to have Rem-Like Sleep and May Even Dream, 2022