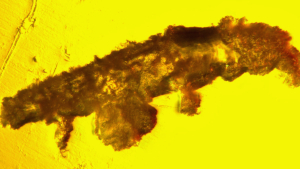

What is striking in the laboratory of Christian Rinke is the frighteningly loud crunching of worm-like larvae that eat their way through styrofoam and dig into blocks of plastic foam. Before throwing away a chewed-up block, the microbiologist holds it to his ear to listen for stragglers. "If the worm is still eating in there," he says, "you can actually hear it.«

Rinke and his colleagues called the larvae of Zophobas Morio, the big black beetle, because of their size "super worms". They feeded the animals with plastic to find out whether the microbes and enzymes in their intestine can provide information about how the dizziness of plastic waste can be broken down on the planet. The result: These superworms manage to survive only with polystyrene. The fabric also called styrofoam is used in a variety of products. This ability of the worms indicate that it is very efficiently broken down in the digestive tract of the animals. "They are basically feeding machines," says Rinke, who works at the University of Queensland in Australia and is a co -author of the study, which was published in "Microbial Genomics".

In order to investigate how the intestinal microbiome of the superworms reacts to pure plastic food, the researchers divided 135 of the animals into three groups: one group was fed only with wheat bran, another exclusively with soft polystyrene, and the third received nothing. All worms were monitored for cannibalism, and the members of the starved group were isolated from each other. The larvae fed with bran were significantly healthier than their plastic-fed or starved counterparts and were able to more than double their weight in the three weeks.

After that, some of the worms from each group were separated to grow into beetles. Nine out of ten animals fed with bran growing up successfully and kept the most diverse intestinal microbioma of all three groups. The larvae feeded with plastic increased less - but still more than the starved worms - and two thirds of them developed to be beetle. Obviously polystyrene is a bad food for the larvae, says Rinke. But it seems as if they could at least gain some energy from the material.

The intestinal bacteria break down the plastic into smaller molecules

This is probably due to a symbiotic relationship between the super worm and its intestinal bacteria. The worm shreds the plastic, the bacteria can dismantle it and disassemble it into smaller molecules that are easier to digest - or possibly one day to be recycled for the production of new plastic, says Rinke. The exact knowledge of the bacterial enzymes is the golden entry ticket to reproduce the process on a large scale in the future.

In order to identify these enzymes, the scientists seized the genome of organisms in the intestine of worms. "With the help of metagenomics, we can actually characterize all the genes in the microbiome [of the digestive tract]," says Rinke. Earlier studies with other insects were not so comprehensive and only focused on one or two possible intestinal bacteria or enzymes, explains the biologist.

Uwe Bornscheuer, head of the Chair of Biotechnology and Enzyme Catalysis at the University of Greifswald, has been waiting for such data since it became clear for the first time just over a decade ago that some insect larvae can eat plastics that are difficult to degrade. The work now published is "the first solid study in which the metagenome was studied," says Bornscheuer, who was not involved in the work, but has been following this area of research.

Rinke and his colleagues identified a number of enzymes, from which they assumed that they reduced the polystyrene in the intestine of superworms in a certain order. Bornscheuer pointed out the team that the enzymes would not be able to break the strong bonds between the carbon atoms in the plastic in the assumed order. Based on his feedback, the researchers are now revising the enzymatic processes they propose.

The team around Rinke does not recommend leaving super worms free on landfill or in dirty landscapes so that they eat up by mountains of plastic. Rather, their unique intestinal microbioma could be a key to the development of a chemical process for the biological degradation of the material. The researchers still have a lot of work in front of them. With the help of their metagic data, they want to check what every single identified bacterial enzyme does with plastic and how all enzymes work together. Your goal: Hopefully to find the most efficient way to reduce our plastic waste.

© Springer Nature limitedwissenschaftlicher Amerikaner, 'Superwürmer' fressen — und überleben - Polystyrol, 2022