It was a silent death on August 12, 1883 at the Natura Artis Magistra Zoo in Amsterdam: a lonely Quagga mare died. The last of its kind. At that time, European scientists did not really want to admit that these zebras had disappeared from the Earth with it. Some researchers had even considered quaggas to be a separate species of the horse genus; and for a while the zoos in Europe hoped that somewhere in southern Africa a lost herd of the animals would still appear. In 1900, the chroniclers of the extinction of species came to the conclusion: this is no longer to be expected.

In the previous decades, the Quaggas in the south of Africa had been hunted by European settlers. They were shot so that they did not contest the grazing land to capture the meat and fur or just to sport. As early as 1840, the British hunter William Cornwallis Harris wrote in his records from the Cape that "this animal was once very often found in the colony, but now disappears in the face of the advancing civilization".

March Turnbull does not recognize anything civilized in the rapid, thorough extermination of animals. "No one gave a thought to her. They had no value and were therefore destroyed in an unnecessary, pathetic way, " says the spokesman for the "Quagga project". It was founded in 1987 with the aim of bringing the extinct species back to life.

The quagga is one of the animals featured in Lost Animals, extinction in August 1883: pic.twitter.com/arkybsr55k

In autumn 2021, almost 140 years after the death at the Amsterdam Zoo, the project members celebrated the birth of a herd member on the photo sharing service Instagram: "Finally. After two years of waiting, Nina has given birth to a foal of the best quality." For Turnbull, this is another of many laborious steps on the path of "feasible correction of a historical injustice".

Conflict between the new and old stepzenbra

Critics see it differently. It is not even clear how the newborn foal of a "rough quaggas" is to be classified scientifically and whether it can make a biologically or ecologically valuable contribution. "As a conservation ecologist, I have strong reservations about the project," says Graham Kerley of Nelson Mandela University in Gqeberha, the former Port Elizabeth, South Africa. It is only possible to breed back an animal that superficially corresponds to the appearance of the extinct quaggas. "We have no idea of other possible differences, especially with regard to the complexity of behavior and physiology," says Kerley.

During the regression or image breeding, attempts are made to at least create an extinct species, subspecies or breed externally, in which individual animals are mated with each other of a close-related, living species. The goal is to get the extinct model as close as possible to the extinct model, so you choose animals with a similar exterior for breeding-such as quilting bras to breed rough quaggas.

Genetic makeup and phenotype

The genotype represents the totality of all the genes of an organism. The sum of all the characteristics of an organism is called the phenotype, which, depending on the organism, is decided in different proportions either by the genotype or by environmental influences. Among other things, researchers use genotypic and phenotypic differences to classify species and subspecies. Such phenotypic features in animals can be, for example, their size, the strength of limbs, the formation of fangs or coat pattern and color.

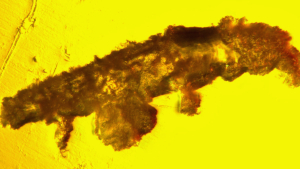

The quaggas of the past looked as if the stripes were fitted from the shoulder from the shoulder down from the shoulder, so that they completely disappear over the fuselage to the rear of the animal.

They were then replaced in the fur pattern by different dark brown tones.

The new rough quaggas should also take this look.

»To illustrate our goal: We are concerned with getting a sufficiently large and survival-capable herd, so to speak, convincing rough quaggas.

Every copy of it should-if you take a journey through time as a thoughts-without noticing in a herd of the old original quaggas, «explains Turnbull.

The project is far from that far: only a few of the currently 109 animals would not have been noticed under real quaggas. Especially the brown coat color caused the breeders difficulties for a long time, and only now are there increasing successes here. One counts "ten convincing copies at the moment," says Turnbull. In addition, there are other animals that farmers in South Africa have bred privately, outside the actual project. In total, these various programs bring it to 200 Rau-quaggas nationwide, 20 of them with the rating "convincing".

The Natural History Museum as an inspiration

The idea for Quagga backing originally goes back to German natural historian Reinhold Rau, who died in 2006. From 1959 Rau had worked as an animal preparator for the South African Museum in Cape Town and was inspired there by a Quagga foal preserved in the museum. He was convinced that the animals would not represent their own biological way. In search of documents, he traveled to Europe in 1971, examined 22 other stuffed quaggas and took tissue samples. They were finally genetically analyzed in 1984 by a team around Russell Higuchi at the University of California in Berkeley, whereupon the Quaggas were finally classified as a subspecies of stepping bras. In 2005, the University of Uppsala confirmed this classification with now more mature genetic examination methods. Rau had long since launched the Quagga project in South Africa: he had started with a small herd of steppe bras from Namibia, the fur pattern of which had a certain similarity to the low-striped Quaggas. For breeding, he went to pair particularly suitable stallions with other quilted bras in such a way that the Quagga characteristics from generation to generation emerge more clearly. This is how the line of the rough quaggas was created.

For Graham Kerley, however, these animals have nothing to do with a natural or even wild species: "With such selective breeding, there is clearly no quagga coming out – but a domesticated form of steppe zebra. Domestication is the result of artificial selection." The process also entails a high degree of inbreeding and thus "significant losses of genetic diversity". Rough quaggas could also pose a danger to wild zebra populations if they are released into the wild: mixing them together is also likely to limit genetic diversity in these populations.

March Turnbull contradicts here: »So far we have had no negative effects through inbreeding. We conduct precise breeding books and know who is related to whom. «Dominant breeding stallions only showed offspring between different herds - a sometimes frustrating approach, which is necessary, according to the project manager:» We had so long problems, a brown To establish fur paint, and so the temptation is of course enormous to bring three or four animals together with a really successful color again and again. But we don't! "

Goal is to have six intact families.

The project is only slowly progressing due to such precautions: the goal of keeping a stable herd of around 50 convincing rough quaggas with sufficient genetic diversity is still far away. "The currently 20 convincing animals in South Africa are distributed over several herds and integrated into the social structures there," said Turnbull. The project also needs an area that is large enough and ecologically suitable to absorb a 50-member herd. It would consist of about five or six stable family groups; One of a dominant stallion and about six to seven mares, as well as some young stallions and semi -adolescents who would search for connection. Under such conditions, however, "each group would produce two to three foals every year", and the moment would have been reached, says Turnbull to "let go" - that is, no longer managing the herd, leaving it and letting it wild.

But for what? Does it need the new, old subspecies? It is controversial whether the subspecies stands out genetically or ecologically, or even both, as some researchers make a condition. Should it be about bringing back an extinct species? "But here you would have a domesticated, inbred zebra instead of a quaggas," says Kersey, who is also a member of the group of specialists for equine species in the World Conservation Union IUCN. And: "If the animals are to take on an ecological role from the past again, why shouldn't Burchell zebras, the southern subspecies of the steppe zebra, simply step in as a replacement?«

A questionable genetic status

In the middle of the long-running dispute about the value of the rough quaggas, a question burst out that actually seemed to have already been answered: Were the original quaggas a real subspecies at all? Even in the 19th century, researchers had even considered the animals as a separate species, due to their geographically separate development and the large phenotypic differences. In an article published in the journal "Nature" in 2018, an international group of genetic researchers now even doubts that quaggas are a clearly distinguishable subspecies from other steppe zebras. The genetic material analysts had analyzed the DNA of 59 steppe zebras of all six subspecies based on morphological differences, including those of the extinct representatives. They come to the conclusion that the genetic structure of individual populations "surprisingly" does not reflect the division into subspecies.

@Whadtheffacts the quagga project in South Africa is recreating the extinc quagga through you selective breeding pic.twitter.com/iy8yyx5h5j

In other words: there are of course visible differences in the shape and appearance of the different steppe zebra subspecies, but the animals in the individual groups are not genetically recognizably more similar than other steppe zebras from other "subspecies". According to him, it "does not make sense to divide the steppe zebra into subspecies at all. According to our investigations, there is no sufficient basis for this, " says population geneticist Rasmus Heller from the University of Copenhagen, who participated in the study.

The phenotypical variations of the quilted bras catch the eye; The strip patterns in particular change with the latitude from north to south, with the extinct quaggas once being the southernmost population. Biologists know those phenomena in which the appearance of a kind differs with the geographical location of individual populations along eco -plaice. How such ecological border lines arise and how they remain stable is still controversial among evolutionary biologists. "I am not convinced that this is well understood and researched in order to use it to take a taxonomic classification," says Heller. And according to his team's studies, it is certain that the Quagga is genetically similar to the other stepzebra sub-species-more similar than the northernmost variant of the quilted bras in Uganda. And this is not even managed as its own subspecies. This should not lead to the extinct quagga as a subspecies.

But does this change the scientific relevance of Rau-Quagga breeding? No, Turnbull and his colleagues think: They would have been rather relieved that the "Nature" study by Heller and Co found such small genetic differences between quagga and other plains zebras. This makes it more likely that the difference in phenotype is also not based on clear genetic differences. As of now, the following must apply: The extinct quagga and today's plains zebras differ above all in appearance. And that's exactly why the breeding project is feasible, emphasizes Turnbull.

Heller, however, warns too much enthusiasm: one has to make it clear "that we do not know which adjustments were developed in addition to the unique phenotype during the quagga".

Maybe you could even do heart for heart.

But »the underlying gene variants could still be present in the steppe bras.

You would have to recombinate it exactly appropriately to create an animal that a quagga would be and not only looks like that, «emphasizes Heller.

Such genetic variations of the extinct animals must first be known in order to be able to exactly formulate the breeding objective of a "true" quaggas.

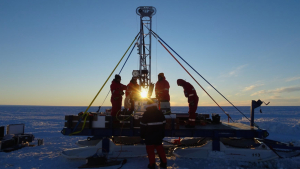

So far, however, the plains zebra researchers do not even understand in detail which genes of the animals are responsible for fur patterns and color. The question is complex, as the research reports of evolutionary biologist Brenda Larrison of the University of California in Los Angeles show. She wanted to clarify how the zebra got its stripes, and came across genetically sophisticated mechanisms. To do this, her team "sequenced the entire genome of an animal from the Quagga project," Larrison reports. It is still unclear which gene signatures play a role – but clearly not only one or a few genes are responsible for the phenotype of the plains zebra, but a whole series.

Another animal getting another chance?

The Quagga project should continue despite difficulties and scientific concerns. Some criticism is justified, admits Turnbull. You can really "never bring the old quaggas exactly back" - or copy the evolutionary steps in such a precisely that identical versions of a species will come out in the end. That is also not the goal: "We want an animal to develop again, but in the end it looks like an animal that has already existed."

Bringing extensive species is often expensive: it is not uncommon for millions to devour highly ambitious "De-Extinction" projects. Shouldn't such sums prefer to be output to keep existing species? »We are all enthusiasts who work free of charge. We may spend 25,000 euros a year, which we do not receive from funding for species protection, «explains Turnbull. The zebra crossing researcher Brenda Larrison believes that it may not make an ecological sense to bring back long -died species - but the Quaggas are a special case. Because they "recently disappeared and belong to an existing way that continues to live in their original habitat". If there is a good candidate for such a project, says Larrison, then it is the quagga. And with a little luck, adds Turnbull, people will one day see our Quagga herds in South Africa and say: "These animals were brought back because we should never have made them disappear."