The two large forest fires from the weekend near Treuenbrietzen and Beelitz in Brandenburg have now been extinguished. Especially rain has brought relaxation. In the meantime, more than 400 hectares had been in flames. The risk of fire in the region has increased significantly in recent years. In 2022 alone, the authorities have already counted almost 200 fires. One of the fires also destroyed part of the test areas of the long-term experiment »Pyrophobic«. Since May 2020, scientists from a total of eight institutions have been investigating what makes forests more resistant to forest fires, heat and drought. Pierre Ibisch, head of the research project, explains in an interview why forests burn poorly, forests all the better, how such a fire spreads – and why controlled fires can even be ecologically sensible.

Mr. Ibisch, more than 400 hectares of forest were on fire in Brandenburg at the weekend. One of the areas was already on fire in 2018. Do we have to get used to it in the future?

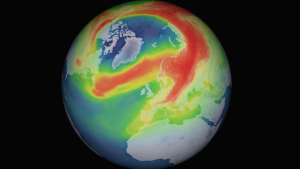

Pierre Ibisch: I'm afraid that with weather conditions like we experienced over the weekend, we are slowly heading – at least in the summer – towards Californian conditions. This is completely crazy, because here in Germany we do not have a Mediterranean climate, but are still in the temperate latitudes. But the maximum temperatures of up to 40 degrees, which we have already measured in Brandenburg pine forests, are hardly inferior to those in California. Unfortunately, people there are already used to forest fires in summer. If it is much too dry for a long time and the vegetation is weakened and a strong wind is added, then it becomes dangerous.

What makes Brandenburg a particularly fire-prone federal state?

The country is very shaped by pine monocultures. More than 70 percent of the forest areas are forest that dominated by this one tree species. They now turn out to be dangerous fire sets - because of their easily flammable, resinous wood and their needles and the low resistance of this monotonous, poor ecosystem. It has already burned here in earlier times, but the dimension of the risks is now different. Long dry periods encounter hot winds and on floors that cannot hold water. No forest burns here, but a forest - that is a difference.

To what extent?

Even if you like to use the terms synonymously, we try to differentiate since now. A forest is a very strong cultural landscape changed by humans, in extreme cases as with the pine a tree plantation. The soil is plowed before the initial reforestation, the pines are planted in a row - all of them, equally old, equally large, of the same type. A forest, on the other hand, grows naturally and at best without an intervention from outside. It is a complex ecosystem, characterized by a high degree of self -organization and self -regulation. Nature itself decides where which trees grow and how they grow. Natural forests create their own microclimate, deal very efficiently with scarce resources such as water and nutrients. It is different in these pine plantations. This is a bit too short in the current reporting, which focuses very much on climate change.

What do you mean exactly?

Well, in Germany, especially in northern Germany, we actually have no increased risk of forest fire.

Of course, for our climate zones, poorly flammable leaf mixed forests are.

Needle forests do not grow flat here, maybe occasionally in higher mountainous layers.

We have created the risk of forest fire, as I now consciously call it.

What's going on? The trees? The floor? The deadwood?

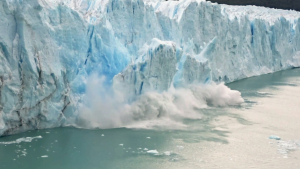

In the intact pine forest, the dry coniferous litter on the ground usually burns first. Such a ground fire does not have to be very intense yet and does not get so hot either. Then it depends on whether the fire hits other fuel and what the weather is like. In strong winds, the flames can flare up higher, capture more bark, then even jump into the crown and quickly get out of control.

You are involved in the research project »Pyrophobic«, which started in May 2020 - also in response to the big fire in the Treuenbrietzen region in 2018. The project is to answer the question of what a fire -strength forest can look like. Are there any first findings?

We are primarily looking at how the areas that have burned are relaxing and which plants settle there. The big question is: How do we come to a forest, the pyrophobic, i.e. firefight, and more resistant than the initial situation? Is that a forest that can resist the extreme conditions of climate change? We examine this on different test areas with different conditions - with and without dead wood, with and without strong soil processing, with and without reforestation. But the new fire last Friday destroyed a considerable part of the research design and many measuring devices. The first results were very interesting: trees settled there on their own, especially trembling poplars, which grew much more effectively than anything that was planted by human hands. In addition, a moss layer and herb plants were already formed that shade the floor and hold water in it. A real microclimate developed. At the same time, it was clear that there could be no fireproof forest within four years. This second fire has now thrown us back. But we are excited to see whether the root networks, such as those of the poplars, have survived the fire and drive it out again.

What if not?

That would be very worrying in the long run. Because if the floor is so damaged that nothing strikes or can settle again, and there are no more trees, the seeds spread, we threaten to stitch. We look at areas in Colorado, for example in Colorado, in the southwest of the United States, where you can already observe it. Fortunately, it has not yet come that far here, but we now have to promote forest development with significantly more financial resources. In my view, easily flammable pine foresters should belong to the past. That must be forbidden.

What could the forest of the future look like? Will we also have to talk about new tree species because of climate change, such as Douglas firs or cedars?

For the time being, I do not see a future for new tree species from warmer areas with us. Our forests are formed by dozens of tree species, some of which are also found in drier and warmer areas. The crucial thing is that we understand a forest not only as a collection of trees, but as a complex system. Native trees have been shown to cope better with a more extreme climate in healthy ecosystems than in heavily used stands. The current strategy must be to buy time with healthy forests until we can think of a sustainable way to combat the climate crisis. Extensive forest areas are relevant in times of drought in order to maintain water cycles. Water evaporates from them, which forms clouds and provides precipitation if they do not come from the Atlantic Ocean.

How can an ecologically sensible and sustainable forest conversion succeed?

That's a good question. We have been talking about this for quite a long time and it is clear that we are not making any progress. There are ecological-biotic obstacles, but above all, of course, socio-economic ones. Forest owners must first of all really want to get away from the pine. But pine trees grow fast, they are the bread tree of the timber industry. Other tree species may not provide the wood that is currently in demand. But that cannot be an argument. What good is a supposedly efficient forest that burns down? You also have to ask yourself how you want to approach forest development. Simply planting new trees does not lead to a proper structural diversity, because then the new plants are all the same age and the same size. Deciduous tree seedlings are also a popular snack with various herbivores. It may therefore have to be hunted more tightly – at least in monocultures – until the ecosystem can better regulate itself.

But this creates new conflicts of interest.

Naturally. It all takes time. Above all, it must be worthwhile for forest owners not only to produce wood, but also to provide other ecosystem services of social relevance - such as cooling and water retention or reduction in landscape fire risks. This must be worth something to society, we need an appropriate fee system.

Can you gain something good from a forest fire – as long as no one is seriously harmed?

A fire as on weekends, of course, not a fire. That scares me and affects me. However, controlled fires may accelerate the forest conversion. We have not yet published this, but a qualitative observation from our project is that after a light floor fire in a pine forest, there is a lot of light pioneering trees such as trembling poplars and birches. In addition, the entire biodiversity increases. We have seen a significant increase in the number of species, across all taxa - in the plants, birds, insects. This creates more interaction, ecological processes are boosted. A fire can give new impulses and, paradoxically, perhaps also lower the flammability in pine foresters.